When San Francisco burned down

Everyone knows that San Francisco was ravaged by flames after the 1906 earthquake. However, it is less known that the city was also destroyed by a series of fires during the gold rush.

No less than six devastating fires devastated the infant city in just 18 months – the largest number of major fires that has ever struck an American city in such a short time.

San Francisco gold rush was a tinderbox. Most of its faint structures were made of canvas, oilcloth, or wood, heated and lit by wood stoves and oil lamps, and ventilated by primitive chimneys or chimneys protruding from the walls of the canvas. Flammable objects were piled up everywhere, heavy drinking and cigar smoking were common, and bad actors had ample motivation for arson.

As Roger Lotchin writes in “San Francisco 1846-1856”, “widespread negligence and malice” were responsible for many flames: “Again and again camphene lamps burst, candles that fell against curtains or fabric walls, or discarded“ sea gars ”set off fires. “Add that the young town’s few cisterns were empty at low tide and that there was no organized fire department, and the wonder is that San Francisco didn’t burn down more often than it was.”

The first of the great fires struck on the morning of December 24, 1849 at 5:45 a.m. It started on the east side of Portsmouth Square in a “hell” of gambling called Dennison’s Exchange. A young Swiss named Theophile De Rutte left a vivid description:

“The cry of ‘Fire!’ so terrifying to the city of San Francisco, built of wood and canvas, reverberating in the air and spreading rapidly from person to person and street to street. … It started between Clay and Sacramento streets. This was the district of the wine and vegetable stalls and also the timber merchants. Alcohol and wood! The most insatiable fire couldn’t have looked for a stronger combination!

“Fed by a strong north wind, the flames made great strides. … It was a terrible yet spectacular sight. With every new rum, brandy, or grog shop it devoured, the intensity of the fire doubled and at the same time it changed its color. It resembled a great display of Bengal lights with tones of red, yellow and blue or a giant punch bowl lit by Satan and constantly stirred by the demons of Hell. “

The fire burned 290 buildings and caused $ 1.5 million in damage. According to Robert Graysmith, in “Black Fire: The True Story of the Original Tom Sawyer – and the Mysterious Fires That Christened the Gold Rush Era in San Francisco,” former New York firefighter and future Senator David Broderick helped keep the flames off stop by blowing up buildings with gunpowder.

But most of the passing gold prospectors that made up the city’s population did not exactly cover themselves with civic fame.

The previous trivia question: What are the chain brakes of a cable car made of and how do they work?

Reply: The chain brake is a block of wood. When pushed onto the track, it slows the car down through friction.

This week’s trivia question: Which San Francisco attraction was Normandy Lane?

Every corner of San Francisco has an amazing story to tell. Gary Kamiya’s portals of the past tell these lost stories and shed light on the extraordinary history of San Francisco in a specific location – from the days when giant mammoths wandered through what is now North Beach, to the gold rush delirium, the dot-com madness and beyond. His column appears every other Saturday.

Do you like what you read? Subscribe to the Chronicle Vault newsletter and receive classic archive stories in your inbox twice a week.

Read hundreds of historical stories, view thousands of stock photos, and sort through 153 years of classic Chronicle front pages at SFChronicle.com/vault.

See more

In his 1850 book, El Dorado, or Adventures in the Road of the Empire, journalist Bayard Taylor writes: “In times of extreme peril, hundreds of idle bystanders refused to lend a hand unless they were paid enormous wages. One of the main dealers, I was told, offered a dollar a bucket of water and used several thousand buckets to save his property. All the owners of the property worked non-stop and were supported by their friends, but at least five thousand spectators stood idly in the square. “

In one pattern, rebuilding began while the ashes were still smoking and within a month there was no sign of the damage.

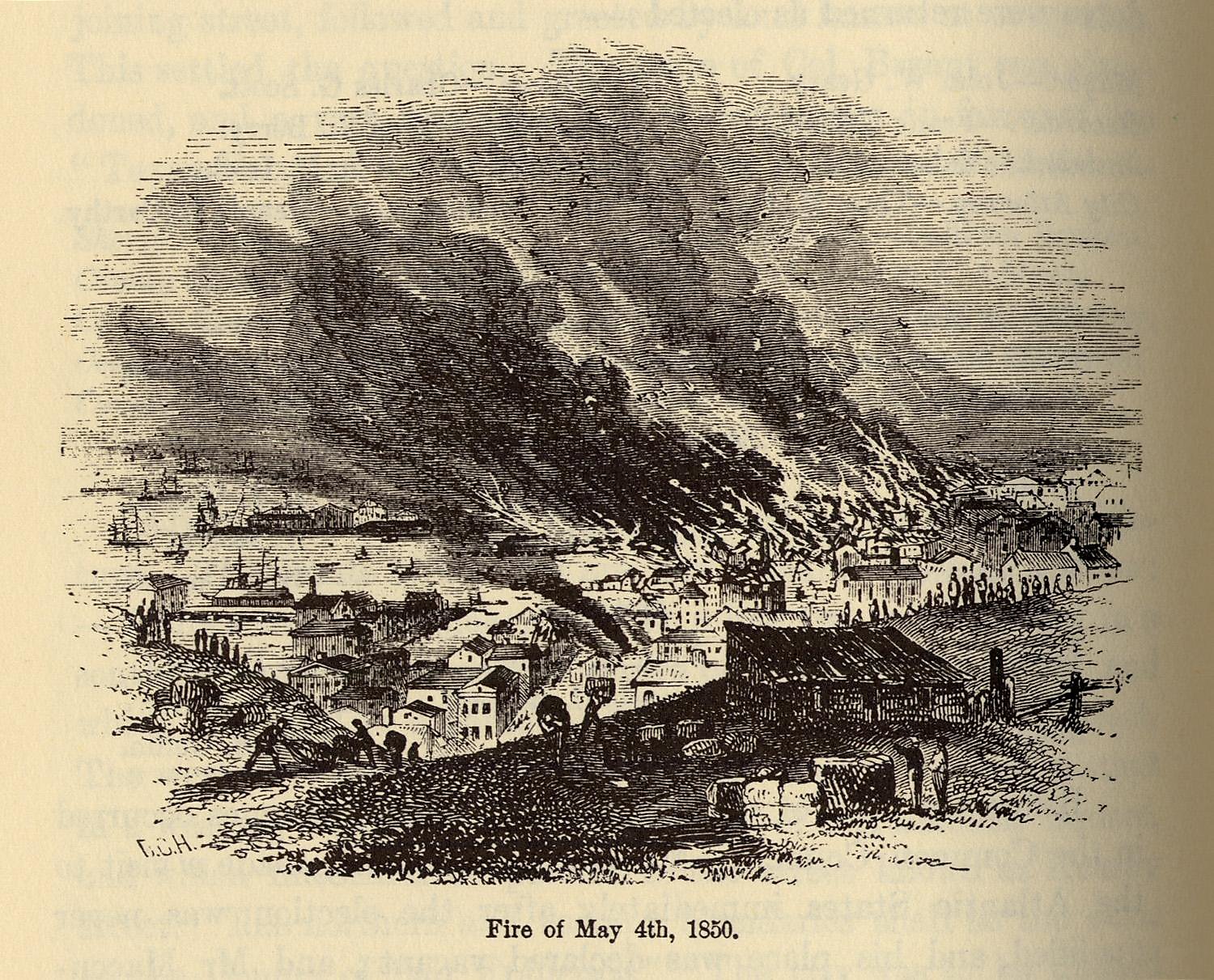

The second major fire occurred less than five months later, on May 4, 1850. That fire also started in the square, consuming 16 blocks and 300 buildings, and causing $ 4 million in damage. Arsonists were suspected and a $ 5,000 reward was posted for information leading to their arrest, but no culprit was found.

Again, bystanders refused to help unless they were paid. According to historian Doris Muscatine in Old San Francisco, a group of men who had volunteered at the time requested payment from the city after the fire. The city council got fed up and instead passed a law requiring residents to fight fires with a fine of up to $ 100. Another law stipulated that each household had to keep six full buckets of water. The city also issued California’s first building ordinance that prohibited the construction of buildings made of cotton cloth.

Rebuilding began even faster than it did after the fire on Christmas Eve: The Annals of San Francisco reported that workers began removing embers and trash from one end of an apartment building while the other end was still blazing. “In a wonderfully short time the entire burned room was covered with new buildings and looked like there had never been a fire there,” continued the “Annals” before adding ominously: “It was generally noted that these were even less essential and flammable than those that had just been destroyed. “

The third fire occurred just six weeks later, on June 14th. It started in a broken chimney in a bakery, raged for three days, consumed several hundred buildings and caused losses of nearly $ 5 million. The fourth followed by three months.

The fifth of the great fires was also the largest. It erupted on May 4, 1851, the anniversary of the second, and burned the entire business district of the city. 16 blocks and between 1,500 and 2,000 buildings were used up. The damage was estimated at $ 12 million.

The sixth fire occurred just a month later, causing losses of $ 3 million. This was the last of the great fires in the gold rush era – afterwards, improved building materials, cisterns and fire fighting techniques helped prevent further disasters.

Estimates of the combined death toll from the 18 months of the fires range from 300 to over 1,000, with most perishing on May 4, 1851. Some unfortunate people who bought “fireproof” metal houses were roasted to death when the intense heat swelled the houses and made it impossible to open the doors.

After the first fire, it was clear that the city urgently needed a fire brigade. At a mass gathering in Portsmouth Square, three volunteer engine manufacturers were organized – the start of a unique and popular San Francisco institution. The colorful and competitive history of the early city’s volunteer fire service companies will be the subject of the next portals.

Gary Kamiya is the author of the bestselling book, Cool Gray City of Love: 49 Views of San Francisco, which won the Northern California Book Award for creative non-fiction. His new book with drawings by Paul Madonna is “Ghosts of San Francisco: Travels through the Unknown City”. All material in Portals of the Past is original for The San Francisco Chronicle. To read previous portals in the past, go to sfchronicle.com/portals. For more features from 150 years of The Chronicle’s archive, visit sfchronicle.com/vault. Email: metro@sfchronicle.com