The secrets and techniques of the San Francisco Columbarium

Most people in the Bay Area are familiar with the oft-repeated fact that the Colma has more corpses than live ones – it’s true and it’s not even close. Established in 1924 as one of the only necropolis in America, the city has a living population of about 1,700, but about 1.5 million corpses.

The reason the small town a few miles south of San Francisco is a large cemetery is because of the mass movement (and rather cruel movement) of bodies that took place a century ago.

But a beautiful San Francisco building tucked away at the end of a cul-de-sac north of Golden Gate Park is still a holdover from a time when the city was covered with graves.

1of3

A woman looking west in Odd Fellows Cemetery in the 1900s. The columbarium can be seen on the right.

OpenSFHistory / wnp15.208.jpg

2of3

2of3

The Columbarium, 1 Loraine Court, San Francisco.

Andrew Chamings3of3

A “columbarium” is a building that houses cremated remains in memorial niches. Unlike traditional in-ground burials, where a granite headstone may only contain a name and dates, cremation niches display personalities, hobbies, and passions surrounding the urn.

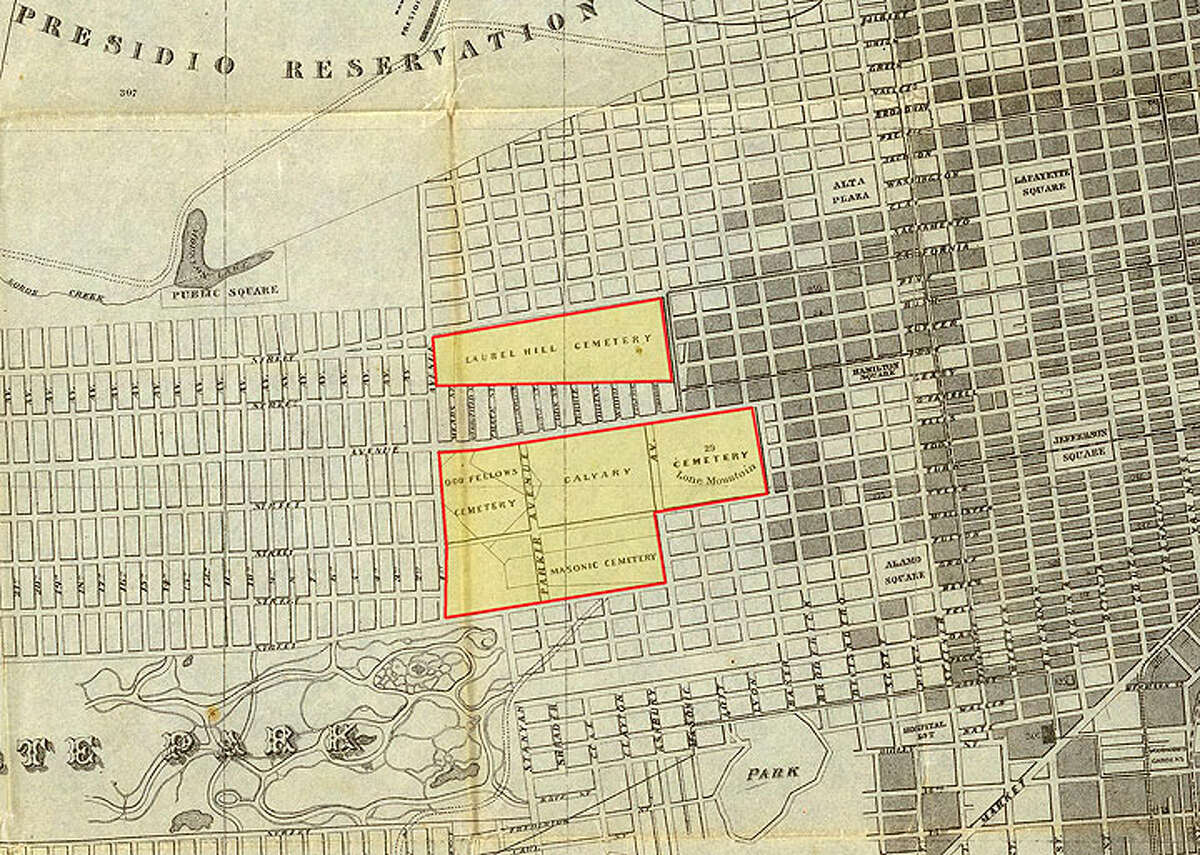

When the San Francisco Columbarium was built in 1897, the great neoclassical depot for human ashes was in Odd Fellows Cemetery, one of four huge cemeteries inside Richmond – Laurel Hill to the north, Odd Fellows to the west, Masonic to the south, and Golgotha to the east . The cemeteries were filled with corpses not long after they were founded, and the columbarium provided an efficient way to house deceased San Franciscans.

If you live in Inner Richmond now, from California to Turk and from Presidio to Parker Avenue, chances are your home is above the final resting place for San Franciscans of yesteryear.

Inner Richmond’s four great cemeteries, seen here on an 1870 map.

Dave Rumsey

Odd Fellows was one of 30 cemeteries in San Francisco at the time – including a Jewish cemetery in what is now Dolores Park, the huge Golden Gate Cemetery near Land’s End, and the city’s first cemetery, Yerba Buena Cemetery, which is located is now Civic Center BART.

1900s San Francisco was not a clean place, and the acres of cemeteries were neither safe nor sanitary. Most of the sites already ran out of room for more bodies, and coffins weren’t always used, leading to some archive reports of children finding body parts while playing among gravestones and mausoleums.

One of the most curious concerns of the residents was the eerie activity in the Chinese cemetery near Point Lobos. History has it that during funerals, Chinese residents often leave delicacies and meat on the tombstones of loved ones to feed the spirits. Opportunistic tramps would walk through the cemetery at night and enjoy the offerings.

Charles Caldwell Dobie’s 1933 book “San Francisco: A Pageant” states: “On a previous day, the cemetery was the meeting place for ghoul-like hoboes who indulged in roast pork and sweets after the mourners disappeared.” This cemetery is now the Lincoln Park Golf Course, and while the flesh-strewn graves have long since disappeared, Chinese gravestones can still be seen on the 1st and 13th fairways.)

The problem became a major controversy at the time, and in 1900 Mayor James D. Phelan signed an order “prohibiting the burial of the dead in the city and county of San Francisco.”

It was officially illegal to be buried in San Francisco. Or as a later examiner story went: “The funeral became as unlawful as peddling drugs on Eddy Street.”

The newspapers wrote of stolen skeletons and the poor city camping about the dead. Column Inch sensationalized the problem in order to promote development in the countryside. Headlines included “Criminal Elements Use Tombs” and even “Vaults Now Headquarters for Drug Addicts”.

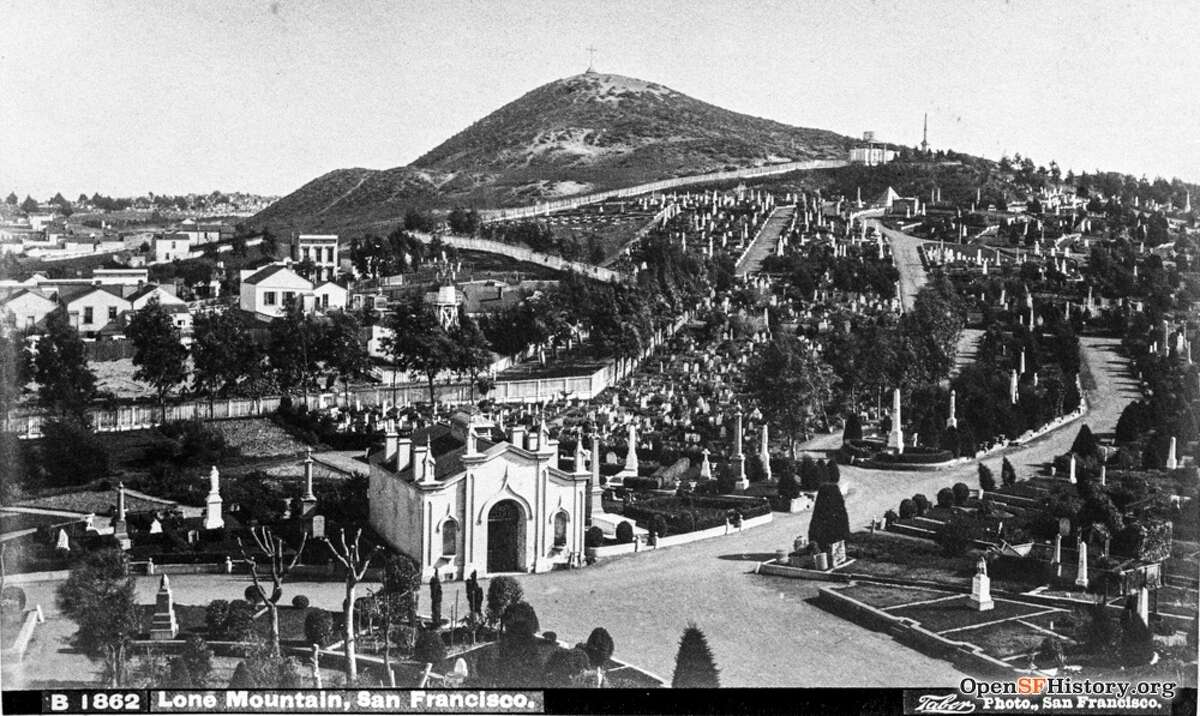

View of Lonely Mountain from the Columbarium, San Francisco, 1862.

OpenSFHistory / wnp37.01340.jpg

It took decades of political battles, with real estate developers scrutinizing acres of house-ready land against the church to decide what to do with the cemeteries that had become a nuisance to the city.

It was finally decided to remove the buried bodies from the four major cemeteries outside the city limits, and after many more years of city politics, the ugly process of moving thousands of dead across the city limits into San Mateo County began in the late 1930s.

The cemeteries were paved and built upon at the request of the property developers. The crematorium in Odd Fellows, which hit the Columbarium, was demolished along with various mausoleums. Many of the headstones were used to build a dam in the Aquatic Park, and some still line the sidewalks of Buena Vista Park.

Many corpses were left behind; In 1993, excavations for the renovated Legion of Honor Museum in Land’s End uncovered at least 700 bodies, and it is believed that there are many more under Lincoln Park Golf Course.

Although the columbarium survived the demolition of the cemeteries, the ban on cremation in the city meant the landmark had no means of generating income, and it fell into disrepair for many decades.

In 1972 the auditor wrote about his shabby condition and the lonely janitor watching the urns.

“A white-haired man is sitting behind a desk waiting for the phone to ring … a couple of old pigeon feathers lie next to some metal containers huddled in a corner.” The white-haired man was Claude Fuller, who alone manned the Columbarium’s office part-time, surrounded by tin cans full of ashes in a large, dusty building the city had long forgotten.

“He looks at the clock, yawns and looks out the window in the direction of the Columbarium,” wrote the newspaper, “which also seems to be waiting for the waiting time.”

But the building was again saved for the dead from the fate of the long-forgotten surrounding buildings when the Neptune Society of Northern California purchased it in 1980 and restored it to its present ornate state. And in 1996 the building was added to the register of San Francisco Designated Landmarks.

The Columbarium, 1 Loraine Court, San Francisco.

Andrew Chamings

After much of the coronavirus pandemic closed the Columbarium, it is open to the public again. As you step in, a silence fills the sacred space as the 45-foot rotunda centers the three-story structure above you. Eight rooms surround the main atrium, named after mythological winds.

The urns on display range from Harvey Milk to the “Muppets” writer and puppeteer Jerry Juhl to Carlos Santana’s father, the violinist Jose Santana. Six beautiful glass windows with angels and religious figures filter the San Francisco sun into the 123-year-old landmark.

Strolling through the Columbarium and its beautiful memorial garden is perhaps one of the most peaceful things to do in San Francisco today.

It is still illegal to be buried in San Francisco, and the building is still the only cremated remains depot in the city, along with the Presidio Military Cemetery.

The hidden landmark is currently available for more remains, but the baroque dome, hidden alcoves, and spiral staircases are likely worth a visit before you die.