San Francisco activist Cleve Jones to vacate Castro flat amid housing battle

Cleve Jones, the LGBTQ activist whose possible eviction from his rent-controlled Castro apartment became a symbol of San Francisco’s housing issues, said he has decided to move out of the flat he’s called home for 12 years by the end of April.

“My physician, my family, my friends all said to me that this is not worth it, this fight to hang onto a place that … doesn’t feel safe” because of a contentious relationship with the new landlord, who will be living upstairs, Jones, 67, said. “I have limited energy and important work that brings me joy. I’m not going to spend the next, who knows how many months, fighting against this woman.”

The situation began when a new owner, Lily Pao Kue, 30, bought the Castro duplex in February for $1,585,000. After installing security cameras, Kue said she had determined that Jones no longer lived there as a primary dwelling because he only showed up briefly over the course of a month. She said Jones’ flatmate Brenden Chadwick appeared to be the sole occupant and termed him an illegal subletter.

Kue invoked the state’s Costa-Hawkins law, which lets landlords raise rent on vacant units to market rate, and notified Jones that she was more than doubling his $2,393 rent to $5,200 as of July 1.

Jones, who is HIV-positive, said he had been protecting his health by spending time in isolation during the pandemic at a house he owns in Guerneville.

San Francisco remains the center of his work, medical care and community, Jones said.

After moving out of the disputed duplex, he will continue to live with Chadwick in the city, Jones said. Chadwick, who shared the Castro apartment with Jones for the past 3½ years, has already found another place.

“He and his dog are my family,” Jones said.

Jones and Kue each accuse the other of harassment, and each said they thought they would prevail if the case went before the San Francisco Rent Board.

Kue, who came to the US as a toddler when her Hmong family was admitted as refugees, said she’s dismayed as being perceived as a rich, entitled real estate speculator, noting that she worked hard to get where she is. She said she wants to live in the upstairs unit and move her mother and grandmother into the downstairs one.

Kue said she is both “mistrustful” and “hopeful” after receiving Jones’ notice to move out, noting that he had previously changed his mind about whether or not to stay.

“I will only be relieved when I’ve gotten my key back without damage done to property,” she said in an email.

Kue says her claim that Jones had already vacated the flat is backed up by Jones’ social media posts about Guerneville and mortgage refinance documents signed in March 2021 in which Jones committed to occupy the Guerneville house as his “principal residence” for at least one year .

Jones said the refi document’s intent was to ensure that he would not rent the Guerneville house to others or list it on Airbnb. He said he has satisfied those conditions while maintaining his residence in the Castro, where he votes, pays utilities and keeps his furniture and possessions. He recently started moving out some items of archival importance to gay history because he feared they could be damaged by construction work Kue is having done upstairs.

Sonoma County property tax records reviewed by The Chronicle show that Jones has never claimed a homeowners exemption on the Guerneville property.

Jones said that he’s among many San Franciscans who cannot afford to purchase in the city, so he turned to a less-expensive area to accumulate some housing security and build some equity. He bought the house in 2018 for $500,000, per public records. He said a little bit of money he made from his memoir, When We Rise: My Life in the Movement, enabled him to do so.

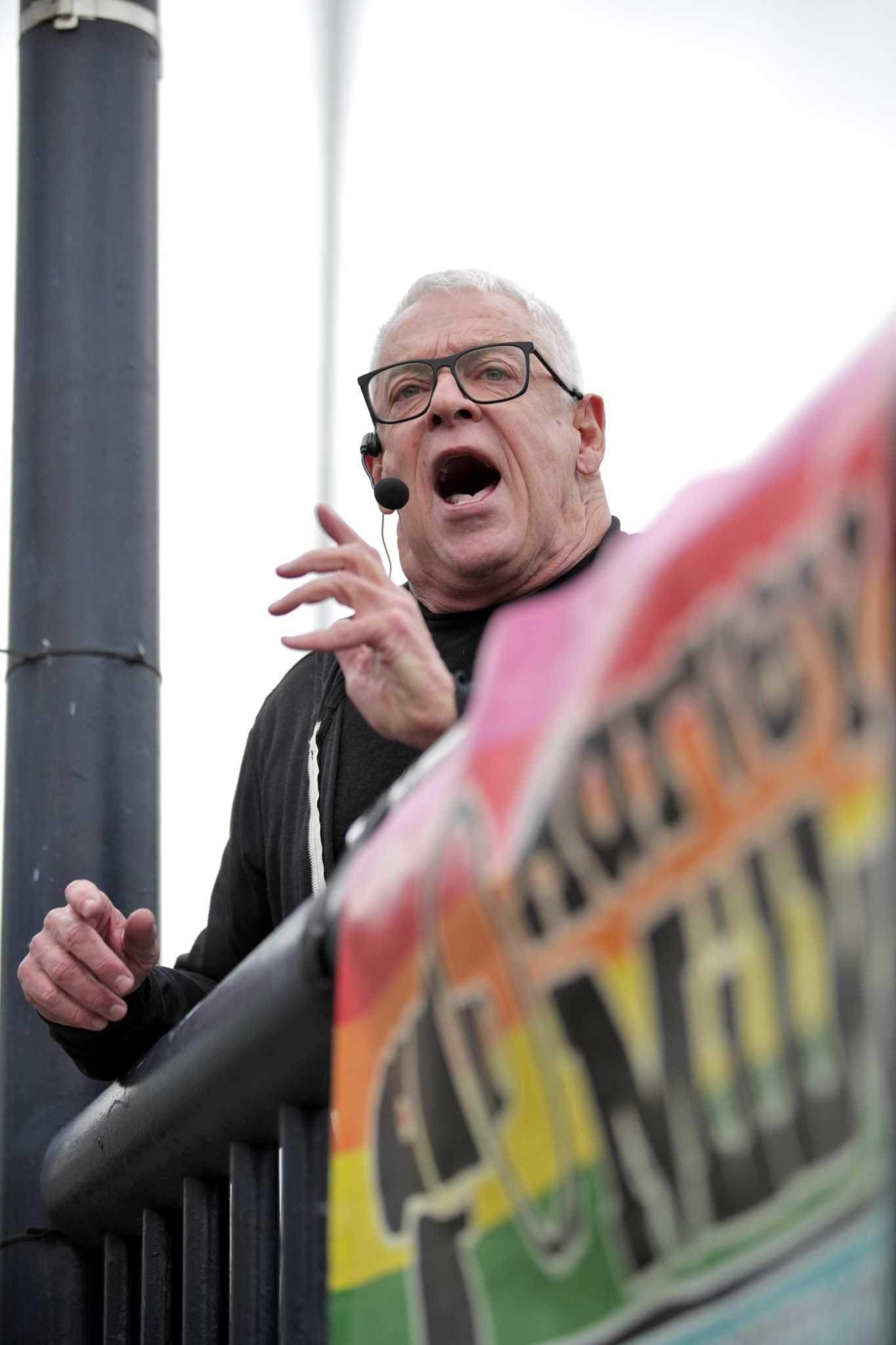

Jones’ situation became a cause celebre, attracting more than 200 supporters, including many well-known politicians, to a rally in his support late last month at Harvey Milk Plaza.

As an organizer with Unite Here Local 2, Jones said he now has additional empathy for the members of the hotel and restaurant workers’ union, who are largely women of color and immigrants, if they were to experience the catastrophe of eviction.

“The only real thing that’s important about my story is not me, it’s not even her (Kue), it’s the reality that with all my unearned advantages of race, gender, the fact that I am politically connected and I do have access to good legal advice, none of that is sufficient to protect me” from the prospect of eviction, Jones said.

As pandemic protections expire, “we’re going to see a small tsunami of evictions coming up,” he said. “Most of those people do not have the resources or support that I have.”

Carolyn Said is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: csaid@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @csaid