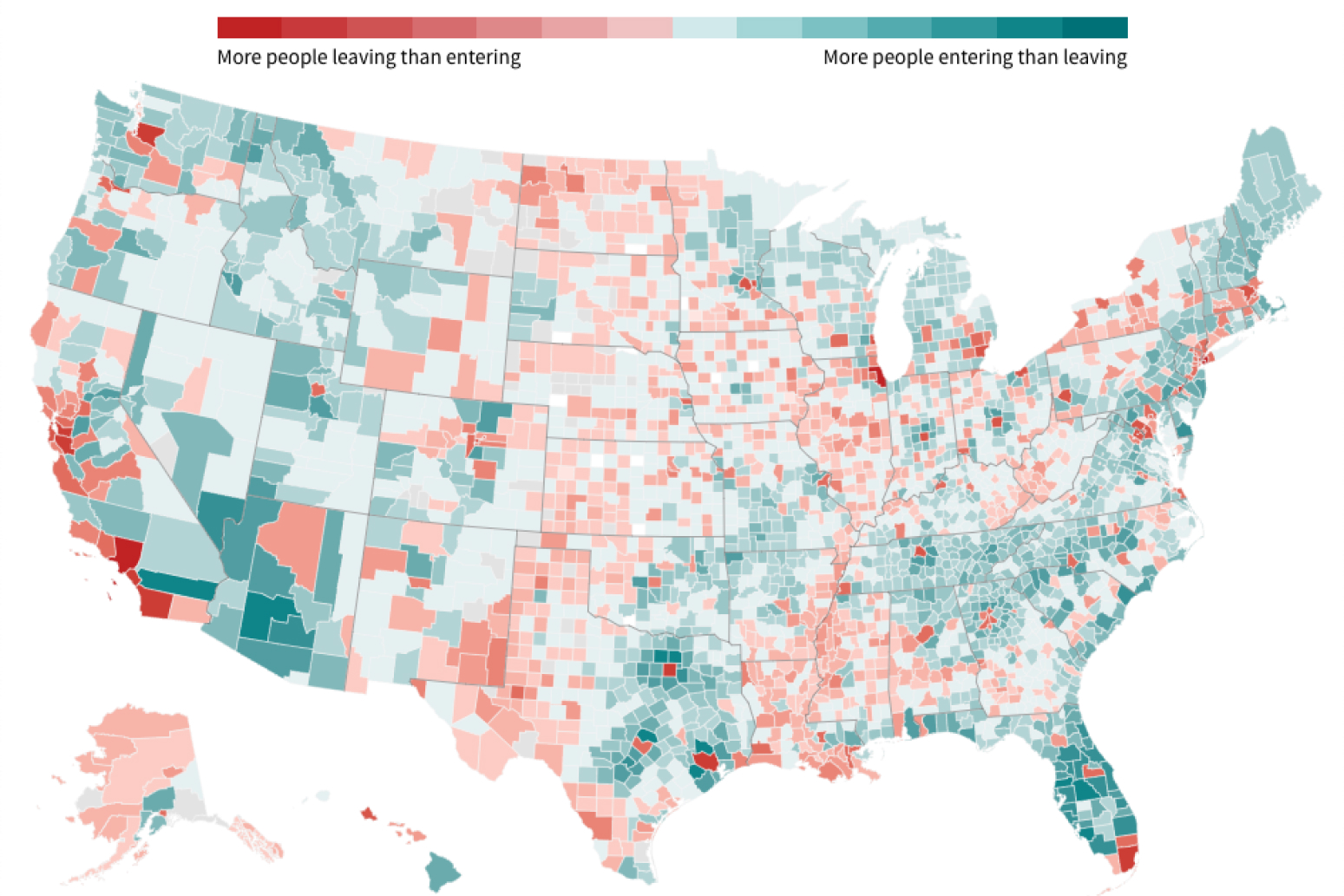

Detailed maps present the place individuals are transferring to and from in San Antonio, Texas and the U.S.

Across the country, the nation’s largest cities have been losing residents, a trend partially fueled by a loosening of in-office work requirements and partially due to rising housing costs. But San Antonio is an exception.

Among the 10 largest cities in the country, San Antonio is one of three that has actually seen population growth since 2020.

Other cities in the San Antonio and Austin metro areas — including New Braunfels, Kyle and Georgetown — have also experienced swift population growth, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The population has grown by about 14 percent in Georgetown, nearly 11 percent in Kyle and 6 percent in New Braunfels between July 2021 and July 2022.

In addition to collecting Americans’ taxes, the IRS collects the most detailed information on where Americans are moving. The numbers take some time to come out — we are just getting statistics for 2021 — but they are a treasure trove of data. The information is based on the reported mailing addresses on tax returns filed to the IRS in 2020 and 2021. By looking at year-to-year changes to a filer’s address, the IRS determines whether or not they moved. The agency then publishes data on the total number of movers between any two counties and their total incomes.

The numbers show that many people moved to suburbs not far from their previous home. But other less-common destinations saw spikes in inbound migration during the first year of the pandemic, with some counties seeing more than twice as many people move in than in previous years.

Former Bexar County residents mostly stayed in Texas, and about 6 percent who did leave the county — just above 5,000 people — moved right next door to Guadalupe County. Another group of about 5,000 former residents moved to Comal County.

The traffic wasn’t just from Bexar County to Guadalupe County. More people moved from Guadalupe County to Bexar County than any other single location, according to the IRS data.

Counties that are home to other large cities in Texas, including Houston, Austin and El Paso, accounted for a combined total of 7,186 new Bexar County residents.

El Paso County in Colorado, which is home to Colorado Springs, was the most popular destination for Bexar County emigrants who moved outside of Texas.

Curious about where people from your county moved to? Search for your county in the interactive below to see the most common origins and destinations for people who moved in and out of your county between 2020 and 2021.

More than half of Texas’ 254 counties saw stronger growth in residential populations during 2020-21 when compared with pre-pandemic migration trends.

For instance, Comal County added 11 percent more new residents during 2020-21 compared to the yearly average of the county’s immigrants between 2015 and 2020.

While most counties had a higher number of new residents, about 27 percent of Texas counties had increased numbers of people leaving the respective county.

That said, 48 counties — about 20 percent of the state — had an increase in both inbound and outbound migration. Blanco County had a 46 percent increase in the number of new residents compared to the yearly average between 2015 and 2020. But the county also had a 20 percent increase in the number of people leaving.

In addition to migration data, the IRS also publishes the reported total income of people moving between counties. Using this information, we calculated the net income change for each county — the difference in total income of people moving in and those moving out. We also calculated the average household income of movers by dividing the total income by the number of filed tax returns per county.

Net income changes largely follow net migration trends. Counties with net population increases in 2020-21 typically gained income, while counties with overall population declines generally lost income. For instance, New York County’s population fell by 63,000 people in 2020-21, resulting in a net income loss of $16.5 billion. Meanwhile, Palm Beach County in Florida had 12,000 more people enter than leave the county and an overall income gain of $7 billion.

Travis County, Texas is an exception to the rule. Despite a population decline of 8,000 people, those who moved to Travis reported higher incomes ($6.5 billion in total) than those who left ($4.7 billion) — a difference of $1.8 billion. On average, households that moved to the county reported incomes of $120,000, while those that left reported $86,000.

About 70 households moved from Bexar County to Palm Beach County in Florida, taking with them an average annual income of about $160,000 each.

While those households had the highest average income of Bexar County emigrants, hundreds of higher-income Texans remained in state. About 1,000 former Bexar County households with an average income of $130,000 moved to Kendall County, just north of San Antonio. Another 200 with the same average income moved to Kerr County, just northwest of Kendall County.

Former Bexar County households with lower incomes also stayed in Texas. Specifically about 500 moved to Wilacy, Bee, Walker, Maverick, Liberty, DeWitt and Karnes counties. The average annual incomes of those households were $34,000 or less.

People from outside of Texas did bring their wealth to Bexar County. About 43 households came from San Mateo County, California, just south of San Francisco. These households had an average annual income of $260,000.

King County, Washington, home to Seattle, and San Francisco and Santa Clara counties in California had nearly 500 households move to the San Antonio area, bringing with them between $140,000 and $180,000 in average annual incomes.

Lower-income families also came from California. Specifically, 26 households with an average income of $25,000 moved from Merced, a county in the middle of the state.

It’s important to note that the IRS data provides only the total income, so it is possible that some of the outliers are driven by one particularly higher-income of lower-income household moving from one county to another. We’ve included only cases where at least 50 households moved between counties to account for that, but a very rich or poor family still might skew the results.