CHP making drug arrests in S.F. with tactic metropolis is making an attempt to ban

California Highway Patrol Sgt. Ryan Burns was leaving a routine drunk-driving bust on Polk Street Monday when a beat-up Chevy Camaro two blocks away started racing through the Tenderloin.

One of Burns’ motorcycle officers had tried to pull the driver over for a flat rear tire and heavily tinted windows, and instead of stopping, the driver gunned it.

“Start me a second unit!” the officer yelled over the radio. Burns hit the gas to join the chase and the driver careened to a stop several blocks later on Gough Street. The officer wedged his bike at the car’s front window, whipped out his pistol and pointed it at the driver’s face, yelling, “Show me your hands!”

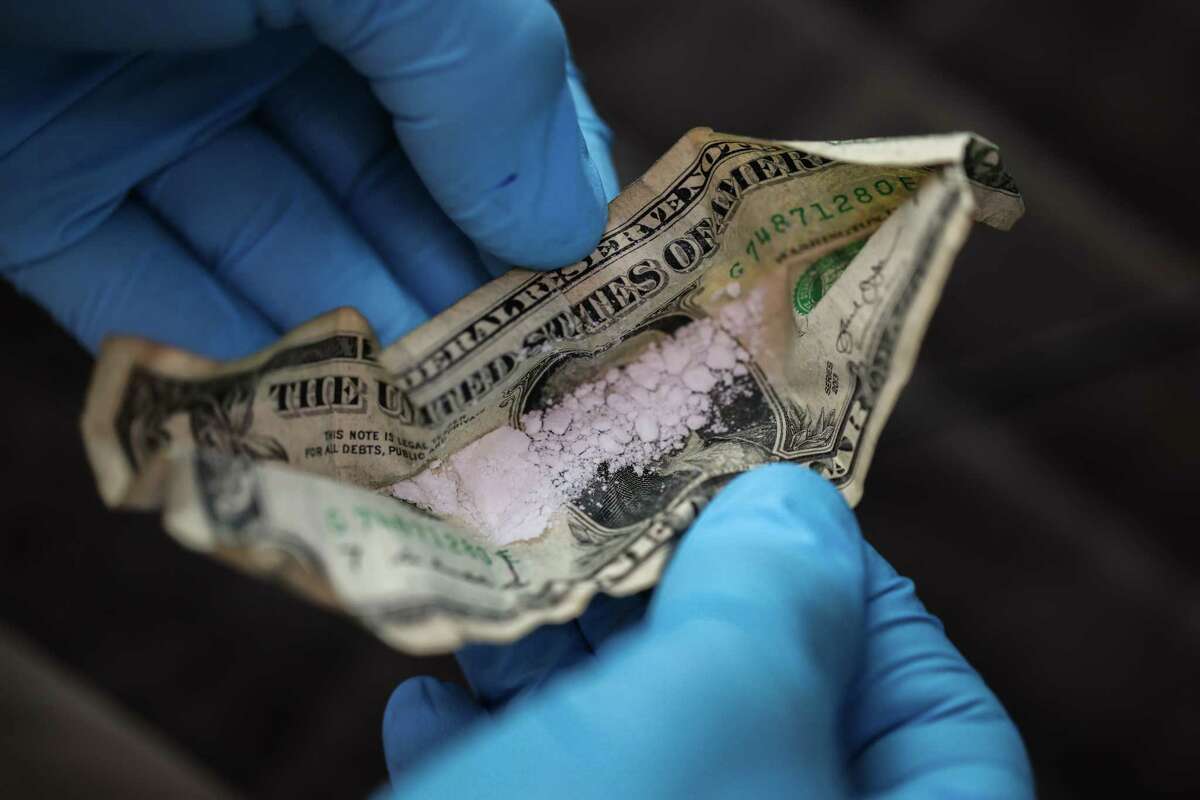

Burns’ partner, Officer Andrew Barclay, dashed over, saw something in the driver’s mouth and ordered him to spit it out. Out flew a tightly folded dollar bill filled with what looked like crack cocaine. Two San Francisco police narcotics officers who happened to be nearby arrested the man for drug possession and evading police.

The scene outside of CHP Sergeant Ryan Burns car in the Tenderloin in San Francisco, Calif., on Monday, June 12, 2023.Gabrielle Lurie/The Chronicle

Traffic stops like this are what CHP officers said they’re hoping will tamp down the rampant, open-air drug trade in San Francisco in a coordinated federal, state and local push that began May 1. That’s when Gov. Gavin Newsom deployed six to 10 CHP officers a day to patrol the Tenderloin and South of Market and 20 California National Guard analysts to gather intelligence for drug-trafficking investigations.

But the crackdown has brought questions, including whether arrests can make a difference in a crisis driven by addiction and whether it’s appropriate to turn loose CHP officers not subject to the city’s oversight.

In the first six weeks of the operation, the CHP seized 5.5 kilos of drugs and made 92 felony and misdemeanor arrests for alleged crimes related to possession of fentanyl and illegal guns, driving under the influence and domestic violence, among others, the governor’s office said Wednesday.

The biggest change has been in drug arrests. Citywide data from the District Attorney’s Office analyzed by The Chronicle shows that CHP officers presented 12 narcotics arrests to the D.A. in May alone — more than the total number they’d presented over the past 12 months combined.

CHP officer Arellano finds drugs wrapped in a dollar bill which was discovered in the car of a man who was trying to flee from CHP on Gough Street in San Francisco, Calif., on Monday, June 12, 2023.Gabrielle Lurie/The Chronicle

CHP officer Arellano finds drugs wrapped in a dollar bill which was discovered in the car of a man who was trying to flee from CHP on Gough Street in San Francisco, Calif., on Monday, June 12, 2023.Gabrielle Lurie/The Chronicle

To do so, state law enforcement officers are employing an old-school investigative technique that San Francisco wants to limit its own police from employing. CHP officers told The Chronicle they can pull people over for minor infractions like broken tail lights or overly tinted windows — something Barclay, who is a public information officer, likened to fishing.

“You start there and work your way up through information you learn,” he said. “That’s why it’s important to make these stops.”

The San Francisco Police Commission, supported by reform advocates, voted in January to restrict local officers from making so-called pretextual stops, pointing to data showing that such stops cost significant police time and money, seldom prevent crime, and disproportionately target people of color.

The policy is not in effect yet because it’s tied up in negotiations between the city and the police officers’ union, said police commissioner Max Carter-Oberstone, who authored the policy.

Carter-Oberstone told Police Chief Bill Scott in a commission meeting on May 3 that he was concerned that CHP officers conducting traffic enforcement related to narcotics “sounds a lot like pretext stops.” Scott, who does not oversee the CHP deployment, responded that “we have not asked them, nor do we expect them to go out and do pretext stops.” He said the CHP was aware of the city’s pending policy and added, “I don’t think the commission will be disappointed with that piece.”

CHP officer M.Garcia (center) arrests a man for a DUI in the Tenderloin in San Francisco, Calif., on Monday, June 12, 2023.Gabrielle Lurie/The Chronicle

CHP officer M.Garcia (center) arrests a man for a DUI in the Tenderloin in San Francisco, Calif., on Monday, June 12, 2023.Gabrielle Lurie/The Chronicle

Carter-Oberstone questioned the efficacy of focusing on pretextual stops given that “every high quality and respected study on this issue has shown that pretext stops are an incredibly inefficient way to discover contraband.”

A Chronicle analysis conducted last year found that from mid-2018 to mid-2022, SFPD officers were 10.5 times as likely to stop Black people than white people for low-level pretextual infractions.

Barclay, however, said the technique as used by the CHP is deployed carefully — and has been effective. “We don’t racially profile,” he told the Chronicle. “We don’t look at people. We look at violations, and we can have a lot of reasons to stop people.”

A spokesperson for Newsom, Izzy Gardon, said in an email that CHP officers’ ability to use pretextual stops was “absolutely not (a) factor” in calling them into the city. Gardon said Newsom’s intention was to “crack down on crime linked to the fentanyl crisis, hold the poison peddlers accountable, and increase law enforcement presence to improve public safety and public confidence in San Francisco.”

Evan Sernoffsky, a spokesperson for the city police force, said Wednesday, “The SFPD is working with the Police Commission to implement a policy restricting pretextual stops. In general, our policies do not apply to other law enforcement agencies.”

Mayor London Breed, who asked Newsom for help to combat drug dealing, said when the deployment was announced that the intention was to do “something different,” enforce accountability and send a strong message to criminals “holding communities hostage.”

Breed supported the move to limit San Francisco police using pretextual stops, in which police use minor offenses to search for other criminal activity, but not an outright ban on pulling drivers over for various relatively minor traffic infractions, arguing that would jeopardize safety. Her office did not respond Wednesday to whether she supported the CHP using pretextual stops to enable drug busts.

CHP officers have seized more than 4.2 kilos of fentanyl in the Tenderloin and the surrounding neighborhoods, along with 1.3 kilos of meth, cocaine and heroin combined, the governor’s office said. The Drug Enforcement Administration estimates that at least 2 mg of fentanyl is potentially lethal, meaning the amount seized could have killed 2.1 million people.

“I’m proud of the CHP and CalGuard’s lifesaving efforts to shut down the Tenderloin’s poison pipeline and hold drug traffickers accountable,” Newsom said in a statement. “These early results show promise and serve as a call to action: we must do more to clean up San Francisco’s streets, help those struggling with substance use, and eradicate fentanyl from our neighborhoods.”

Neither CalGuard or CHP have said how long they would be deployed. CHP said it has used existing resources from the San Francisco office for the operation and is supplementing regular patrol duties with staff from its Golden Gate division.

Despite an increase in enforcement, residents, business owners and people who use or sell drugs told The Chronicle they have yet to feel much of a difference on the streets. The head of a federal task force working on the operation told the Chronicle that seeing the first improvements would take at least a year’s worth of work.

Scott told The Chronicle last week that CHP’s presence “is disruptive to people committing crimes.”

He also said the CHP’s help has freed up his officers to enforce Breed’s new push to arrest some drug users under public intoxication laws in an effort to get them into treatment — a tactic decried by many health experts as ineffective and harmful to people with addiction. The CHP was training his officers on how to recognize people under the influence last week, Scott added.

“The fact that they’re here gives us a little bit more flexibility to do this type of work,” he said. “It’s very helpful.”

The governor’s office did not provide a breakdown of CHP arrests within SoMa and the Tenderloin alone. But data from the District Attorney’s Office, which includes all arrests presented by CHP to the D.A. citywide for possible charging, shows the CHP presented more drug arrests than in past years.

The CHP’s citywide arrest count of 75 in May isn’t historically high: Before the pandemic, the agency regularly presented that many or more arrests in a month to the D.A.’s office.

Johnny Harris, who uses fentanyl and lives outside, told The Chronicle in late May that the CHP has been visible in Tenderloin hotspots where he buys his drugs, but that the officers’ presence hasn’t made a difference.

“They’re not really messing with us,” he said between puffs of his drug, adding that he can always tell undercover cops by their nice dress shoes.

He said the ramped-up patrols won’t prevent him and his street cohorts from simply dispersing their groups when the CHP or police roll or walk by, then reassembling when the coast is clear.

“Not a chance in hell they’ll make a difference,” he said. “They would have to kill everybody to stop the drug trade around here. This is the most God-less place in the world.”

Supervisor Dean Preston, who represents the Tenderloin, said that “nobody wants folks dealing drugs out there,” but doesn’t believe that sweeps of street-level dealers will make a dent without addressing demand. Supervisor Matt Dorsey, who represents SoMa, welcomed more policing geared at trying to shut down open-air drug markets.

Residents and business owners interviewed by The Chronicle reported uneven impacts, with fewer dealers on some blocks and more on others.

“This is definitely an added resource for the city, for the police department, and I’m really happy that this is happening. However, the issue and the challenges are still here,” said Azalina Eusope, owner of Azalina’s restaurant on Ellis Street and a member of the Tenderloin Business Coalition that prompted Breed to add police in the neighborhood this year.

“I know everybody is doing the best that they can. I just hope we can just buckle down and continue the effort. With that, hopefully we’ll see some results. I have faith,” Eusope said.

Tracey Mixon, a longtime Tenderloin resident and organizer with the Coalition on Homelessness, an advocacy group, said she noticed fewer dealers on Eddy Street last week.

“It was the first time where I was able to walk places and not hear, ‘Mama, what you need? ’ she said. ‘That was finally a little bit of changing, but not a whole lot is going to change, because they have been selling drugs out here for years.’

Mixon doesn’t want dealers to bother her or her 13-year-old daughter, but as a Black woman, she said she has been concerned about being racially profiled by law enforcement.

Both Mixon and Del Seymour, a business owner and founder of nonprofit Code Tenderloin, called the CHP deployment a “dog and pony show.” Seymour said he’d seen patrols ramp up and dealers and users moving as far north as Post Street, above Geary Street, but didn’t believe it would change the drug trade. He did, however, support state coordination to go after high-level drug suppliers.

CalGuard has sent 14 analysts to the federal High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA) task force, and later in the month sent another six to the San Francisco Fentanyl Task Force.

Major General Matthew Beevers told The Chronicle CalGuard has assembled thousands of pages of analytics on drug networks in San Francisco. The guard’s role is to assemble a detailed schematic of who’s dealing dope where, how and to whom in San Francisco — so authorities can then crush that network.

Northern California HIDTA Director Mike Serna said people are coming from all over the Bay Area to buy drugs in San Francisco and estimated the number of dealers at “hundreds.” In order to squash the drug trade, he said, “we have to continue the push for years.”

CHP officers said they’re leaving it to analysts to determine if they’re making a difference. But, as Barclay said: “Personally, I’d like to think we have.”

Reach Mallory Moench at mallory.moench@sfchronicle.com; Susie Neilson at susan.neilson@sfchronicle.com; and Kevin Fagan at kfagan@sfchronicle.com; Twitter: @KevinChron

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/TAL-NEW-SOCIAL-athens-greece-WTG2023-1cd2dcb228cb443e84c91695aa98e308.jpg)