The 1906 Earthquake Survivor Who Fought For San Francisco’s Homeless Inhabitants

“I had an absolute legal title to the cottage,” wrote Kelly in April 1908, “as it was built with the money sent here to San Francisco to rehabilitate the needy and destitute refugees … public land, and it was not right to pay six dollars or some other amount a month to rent these cottages. “

So what exactly had Kelly done that led Relief Corporation to take such cruel and unusual measures against them? It started almost immediately after the earthquake and fire.

Earthquake refugees gather in Jefferson Square while smoke still rises from the 1906 fires. (OpenSFHistory / wnp37.00042)

When city officials asked camp residents to leave the parks, it was one of the loudest objections. Rents in San Francisco had skyrocketed after the fire – they doubled in the unburned Western Addition, for example – and many locals had lost their jobs. The working poor just couldn’t afford to move into a new home.

When city officials urged campers to move out of town to cities with cheaper rents, Kelly spoke publicly about the financial impossibility of doing so. The cash she had to raise for her own money and the daily trips her family made to work in San Francisco were completely unthinkable.

Jefferson Square Camp, north of Turk St. (OpenSFHistory / wnp59.00056)

Jefferson Square Camp, north of Turk St. (OpenSFHistory / wnp59.00056)

Kelly soon led marches and speeches on behalf of her community – in her words, a “solid, honest, hard-working class of people who have never asked for alms and always paid their own way.” She called for cash grants to be distributed directly to the refugees. She publicly criticized warehouse managers, city officials and the Relief Corporation.

Kelly not only pursued the sluggish bureaucracy that prevented the refugees from obtaining their rights, she followed the men at the top of the organizations. At one point she accused “almost every man who held a prominent position in Aid Headquarters” of using aid money to buy expensive cars for personal use. At another, she gave speeches to 3,000 protesters at a banquet attended by city officials. “Let the whole world know,” it said on their banners, “that while we are starving, they will feast.”

Kelly had no qualms about calling these people and portraying them publicly as lamenting, selfish cowards. Kelly later wrote of the attendees at this special banquet: “Fearing we might force entry and partake of their fine menu, they snuck very quietly out of the back entrance of the hotel and drove off in their cars so as not to come back for their banquet to end until the poor, suffering refugees had returned to their cold and drab tents. “

Although Mary’s performance sometimes erred on the dramatic side, her keen sense of injustice was not without reason. Funds and supplies to aid earthquake survivors were sometimes mishandled in a way that served to strengthen the class structure prior to the earthquake. For example, financial support from Relief Corporation was distributed on a tiered system that benefited property owners, business owners and, first of all, well-connected people. The poorest, most hungry and least able to find work often languished the longest.

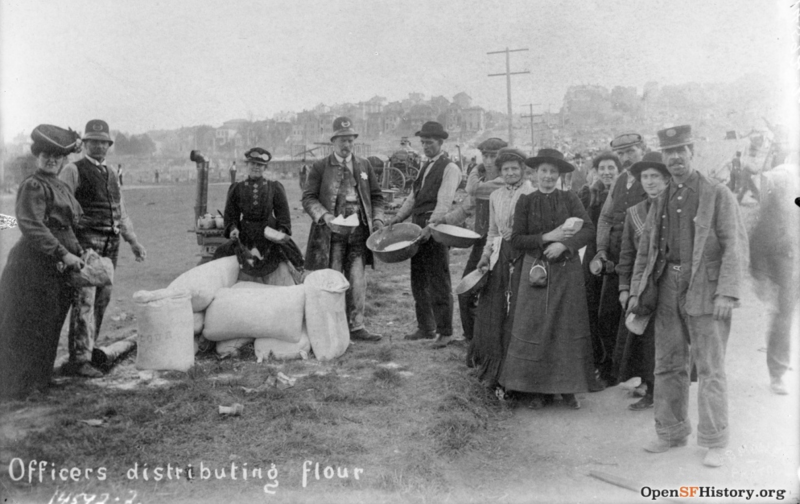

Officers distribute flour near the Moscone Playground (then Lobos Square). (OpenSFHistory / wnp15.1682)

Officers distribute flour near the Moscone Playground (then Lobos Square). (OpenSFHistory / wnp15.1682)

A particularly tremendous example of this came after the Relief Corporation tried to sell some of the flour that was sent from Minneapolis to be distributed to hungry refugees. When donors heard of the company’s intention to sell, they objected. The company responded by dumping several barrels of flour into the bay. It was this kind of vicious mismanagement that prompted Kelly, along with about a hundred other women, to storm the city’s main relief supplies warehouse on July 6, 1906, and leave with 2,000 pounds of flour. “The women said the flour was sent here for them,” reported the San Francisco Chronicle, “and they would take it.” The incident was described by the local press as a “riot” by “angry” women who “didn’t wanted to listen to reason ”.