New Bay Space maps present hidden flood threat from sea degree rise

Amid dramatic ocean waves and flooding atmospheric flows, a new report uncovers a hidden aspect of sea-level rise that has exacerbated Bay Area flooding.

The report, released on Tuesday, maps areas that could be inundated by groundwater that is just a few feet or even centimeters below the ground. This layer of water is pushed up as denser water from the ocean moves inland due to rising tides. On its way up, before the water breaks the surface, it can seep into basement cracks, infiltrate plumbing, or, even more insidiously, remobilize toxic chemicals buried underground.

Communities that consider themselves “safe” from sea-level rise may need to think differently, said Kris May, lead author of the report and founder of the Pathways Climate Institute, a research-based consultancy in San Francisco that helps cities adapt to climate change .

“I started looking at sea level rise, then I’m exposed to extreme rainfall, and then to groundwater … but it’s all connected,” May said. She noted that hotspots where the ground is already exposed to rising groundwater flooding was among the first to occur when a series of atmospheric flows recently brought record rainfall to California: “These giant storms illustrate the magnitude of the risk.”

The new findings are the result of an unprecedented collaborative effort by May, the San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI), UC Berkeley and a broad-based team including regulators, building officials and flood protection agencies to find out where groundwater is located along the bay’s shoreline is close to the surface or is already breaking off. A series of searchable maps available to the public online shows Alameda, Marin, San Francisco and San Mateo counties — the first of many jurisdictions researchers hope will undergo this intense data refinement process.

In this screenshot of the interactive map released Tuesday, the purple areas show where groundwater has already appeared in Marin City and Sausalito. Red and orange indicate where groundwater is within 6 feet of the surface.

(SFEI/Pathways Climate Institute)

The maps are based on a new but growing body of research. In 2020, another study conducted by the US Geological Survey laid the groundwork for this problem along California’s 1,200 miles of coastline, and state toxin control officials have since begun their own mapping efforts to better understand how rising groundwater is affecting contaminated land could.

Similar research into vulnerable communities in Southern California is also currently underway by a team led by Cal State Long Beach and Cal State Northridge.

This emerging risk of flooding raises many difficult questions, but the data to date make it clear that urgent action is needed.

“We really need to focus on where pollutants might be mobilized by rising groundwater because that could have an immediate impact on a six-year-old, a pregnant woman, or someone whose immune system is particularly vulnerable,” said Kristina Hill, a UC Berkeley researcher. who is particularly concerned about underserved communities like Marin City and historically industrial areas like East Oakland, where much of the soil is contaminated. “The [remobilization] could happen now while it’s wet outside.”

When it comes to groundwater, there are two types to consider. One type, which researchers are now concerned about, is the unbound water that collects in the pore spaces of the soil very close to the surface. This is the water that runs off the road and seeps into the ground. The other type, trapped in aquifers hundreds of meters deep, is the water we tap for drinking.

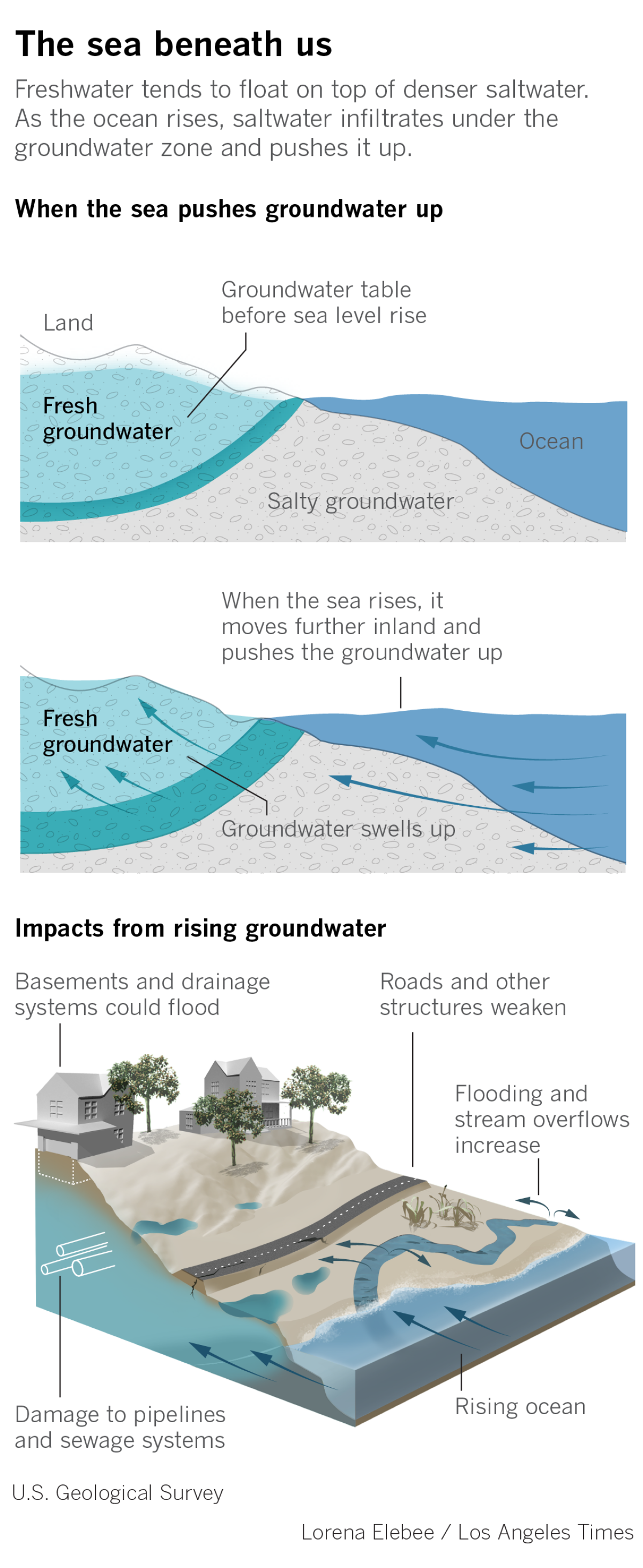

As the tide moves inland, the shallow fresh water tends to float on top of the denser salt water — and is pushed up toward the surface as sea levels rise. Because the shallow groundwater is not consumed, few people have studied this layer of water in California.

(Lorena Iniguez Elebee/Los Angeles Times)

Hill, who directs the Department of Urban and Regional Development at UC Berkeley, first realized nearly a decade ago that this shallow aquifer had been overlooked in talks about sea-level rise. Along with May and Ellen Plane, who is now an environmental scientist at SFEI, she analyzed data from 10,000 wells across the Bay Area and concluded that more than twice that amount of land could be flooded from groundwater if the ocean continues to rise .

Then, in a remarkable move to turn those initial approximation studies into data that government agencies would actually use, the researchers called on officials themselves to help fill in the data gaps. City and county officials searched for geotechnical reports and other potentially useful records that had been archived in different (and often isolated) departments. They went through hundreds of PDFs and spreadsheets to compile all of the underground data that had been collected for building permits and projects.

Public works officials then checked the updated maps against their own observations, such as storm sewers that back up during high tide and roads that tend to flood even when there is no current.

Discover the current groundwater conditions in this interactive map:

Patterns emerged. Many of the communities most exposed to the flooding were built along historic streams or on reclaimed wetlands. If you overlay 5.5 feet of sea level rise on the map, water is expected to flow back into virtually any wetland that has been filled.

Officials in San Francisco are already considering this data when considering new construction projects. Other cities and counties are beginning to reconsider their flood mitigation options—after all, a traditional levee or seawall wouldn’t do anything to stem groundwater as it moves with rising sea levels.

Ultimately, officials need to figure out what to do with all of the contaminated sites along the bay that are still awaiting remediation — or those that need further remediation, said Hill, who has completed another set of maps that will show where and In which direction might rising groundwater remobilize harmful chemicals underground? The commonly used approach of ‘covering’ a toxic waste dump, for example, rather than actually removing the contamination from the ground, may no longer be sufficient.

Regulators at the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board have been following all of this research with keen interest and are already looking at the updated maps, said Lisa Horowitz McCann, deputy executive director. The board recently ordered its long-term flood control plans for 16 bayside landfills to take groundwater rise into account, and caseworkers are now going through hundreds of cases to determine which sites require further action.

“This data gives us the ability to take stronger action — and even legally supports it,” Horowitz McCann said. “We’re looking at a larger universe of cases now.”

Researchers hope to continue this mapping work for the rest of the Bay Area. Next up is Contra Costa County in the East Bay, where a number of historically contaminated sites are being considered for remediation along Richmond’s industrialized coast.

An aerial photo shows a cyclist riding through a flooded bike path in Mill Valley during a royal flood in 2022. Many low-lying areas along the San Francisco Bay are at increased risk of flooding, according to a new study.

(JOSH EDELSON/AFP via Getty Images)

Much more work also needs to be done to understand what the actual damage to gas lines, sewage treatment plants, foundations and other buried infrastructure will be, said Patrick Barnard, whose research team at the US Geological Survey has performed extensive flood modeling by officials across the state used.

“We need to start bringing this information together with the world of technology,” he said. “We built everything assuming the ground is dry. What does it mean that he is now constantly full?”

Barnard has also studied what scientists call “composite extremes.” What do we do when seawater enters at high tide, while our rivers and storm sewers try to flush excess rainwater into the sea and the ground cannot absorb anything because the groundwater also floods?

“We looked at this in a case for the Napa River, and basically an average annual winter storm could turn into a 100-year flooding event when the ground is already saturated,” he said. “Add in any amount of rain, even amounts that are not normally catastrophic…and you have catastrophic effects.”

For Chris Choo, Marin County Planning Manager, the support for the recent mapping effort has been eye-opening in a number of ways. She has spent years helping communities prepare for climate change, and the challenges have grown more complicated as one disaster seems to overwhelm the next.

“From drought to drought to drought to a big concern that we don’t have enough water, all of a sudden, within two weeks, we’ve seen the effects of way too much of it,” she said, not just citing the flooded streets who kept their colleagues working around the clock, but also the heavy surf that swept much of California earlier this month and even split a pier in two.

“People still tend to see these things as isolated terrible things and not part of a collective change…in terms of what the future might hold,” she said. “We live in nature and too often think we’re separate from it… but nature still rules.”