In San Francisco’s Most Polluted Neighborhood, the Polluters Function With out Correct Permits, Studies Say

Raymond Tompkins believes the highly efficient air filters in his old, golden Mercedes are among the best features of the car. They trap dust and tiny particles of dirt and are equipped with activated charcoal to remove odors – an invaluable feature for a longtime resident of the most polluted neighborhood in San Francisco.

“You know I’m supposed to be dead,” said Tompkins, 72. “Most black men don’t live that long here in Bayview. I go to a funeral every month. “

Living in Bayview-Hunters Point, a mostly low-income and minority neighborhood in the southeast of the city, means blinking away the dust from the sand and asphalt hills piling up in industrial yards and ignoring the stench of a sewage treatment plant and animal treatment facility next to it their homes and schools.

A confluence of pollutant sources has dominated the four square mile neighborhood for decades, and a state environmental analysis has identified the Bayview area as the area with the highest cumulative pollution in the city.

State and local authorities should actively seek to reduce pollution in Bayview, local supporters said. Instead, they have continued to allow polluting facilities to operate without definitive permits for the pollution.

Bayview’s Piers 92 and 94, which border San Francisco Bay, were operating a concrete plant and two sand dumping sites in 2017 and 2020 without definitive pollution permits from the Bay Area Air Quality Management District, according to environmental justice reports, at the School of Law Clinic Law from Golden Gate University. The concrete plant is owned by CEMEX Construction Materials and the sand plants were sold to Martin Materials by Hanson Aggregates Mid-Pacific in November.

Although the Aviation District was informed of the alleged violations back in 2017, it has continued to delay enforcement actions and allow most operations to continue as they have been working with the facilities on draft permits.

But more than four years after the Air District contacted the facilities with indications of violations, those permits remain at the draft stage while the facilities continue to operate.

“If you don’t have a permit, the Clean Air Act doesn’t allow you to pollute the environment,” said Lucas Williams, associate professor of law at Golden Gate University and an associate attorney with the Law Clinic. The Clean Air Act, the premier federal air quality act passed in 1963, requires polluting facilities to obtain permits from local air quality agencies.

The aviation district requires polluting facilities to submit completed permit applications within 90 days of being notified by the aviation district of a violation or else they will be prevented from operating – a rule the air district does not enforce, the report said.

Instead, the district allows “longer back and forth” with the permit applicant if he does not provide sufficient information, the report said. This long-standing practice means that permits have been pending for years, while environmentally harmful plants are in operation in the meantime.

Ralph Borrmann, the Air District’s public information officer, said in an email that the agency has delayed approvals because “more information is still needed to better understand the impact on the neighborhood.” The Air District will conduct an environmental review of the facilities to learn more about what the California Environmental Quality Act of 1970 requires, he said.

“Evaluating these projects has been taking more time in the Air District than we would like,” said Borrman. “In the course of this process, the Air District’s rules, guidelines and priorities have changed, which has resulted in some delays.”

He added that the air district “seeks to impose penalties at levels that discourage future violations”.

The Air District filed a complaint with another concrete plant that violated its permit and fined Central Concrete Supply $ 75,000. The district eventually settled with Central Concrete for $ 9,000. Recology, a recycling facility that had operated a concrete crushing operation pending a permit applied for in 2016, closed the business after breaching it in 2021.

The Bay Area Air District regulates stationary sources of air pollution in the Bay Area’s nine counties. For concrete and sand plants, the air district issues permits that limit the amount of throughput or raw material that can be processed over a period of time. The air district also regulates the moisture content of the processed material – material that exceeds 5 percent moisture content is exempt from the permit requirement.

However, the CEMEX concrete plant “regularly” exceeded its throughput without the approval of the aviation district and, according to the Law Clinic, processed up to five times more than its approval limit of 60,000 tons.

Hanson’s two sand and material handling facilities on Piers 92 and 94 have been operating without a permit since 2001. The facility at Pier 94 was initially exempted, but lost the exemption when the Air District discovered the moisture content of its inventory levels dropped below 5 percent.

CEMEX and Martin Marietta did not immediately respond to requests for comments.

Residents are concerned about the health effects of having these facilities operated near their homes and within a few thousand feet of an emergency shelter for the homeless from Covid-19.

Concrete batching plants like the ones on Piers 92 and 94 emit types of fine particulate matter known as PM 2.5 and PM 10, the names referring to particles 2.5 or 10 microns in size. These particles can linger in the atmosphere for weeks and affect visibility. They can also be easily inhaled and penetrate the lungs, leading to negative health outcomes such as asthma, chronic bronchitis, heart attack, and premature death.

Bayview has some of the highest hospital admission rates and the highest number of emergency rooms for asthma in the city, according to a 2016 study by the San Francisco Health Improvement Partnership.

Williams, the law firm’s attorney, said facilities that operate without valid permits should be closed in the meantime rather than just being slapped in the face of fines. Lax enforcement by the aviation district is indicative of a more widespread pattern and practice of failing to protect the Bay Area’s deprived communities, he said.

“The bottom line is that the district should stop building polluting facilities where there are already a lot of polluting facilities,” said Williams.

The air district does not have the ability to close these facilities: That would require a court order or the approval of a hearing committee, Simrun Dhoot, a senior air quality engineer in the air district, said in an interview with Inside Klima Nachrichten.

It’s up to the aviation district to decide whether or not to bring an enforcement action against a violator, said Dave Owen, professor of environmental law at the University of California’s Hastings College of Law, San Francisco. In this case, the aviation district decided that a better course of action than closing a facility is to work with the facility on a new permit, he said.

Keep environmental journalism alive

ICN offers award-winning climate reporting for free and advertising. We depend on donations from readers like you to keep going.

Donate now

You will be forwarded to the ICN donation partner.

But while the aviation district cannot unilaterally decide to cease operations, it “could at least take enforcement action, and threats of a closure order would likely lead facilities to take approvals and pollution control more seriously,” Owen said.

“I think it’s a problem,” he added. “It is not the right way for emitters to work for years with draft permits and in an overburdened community on an industrial scale.”

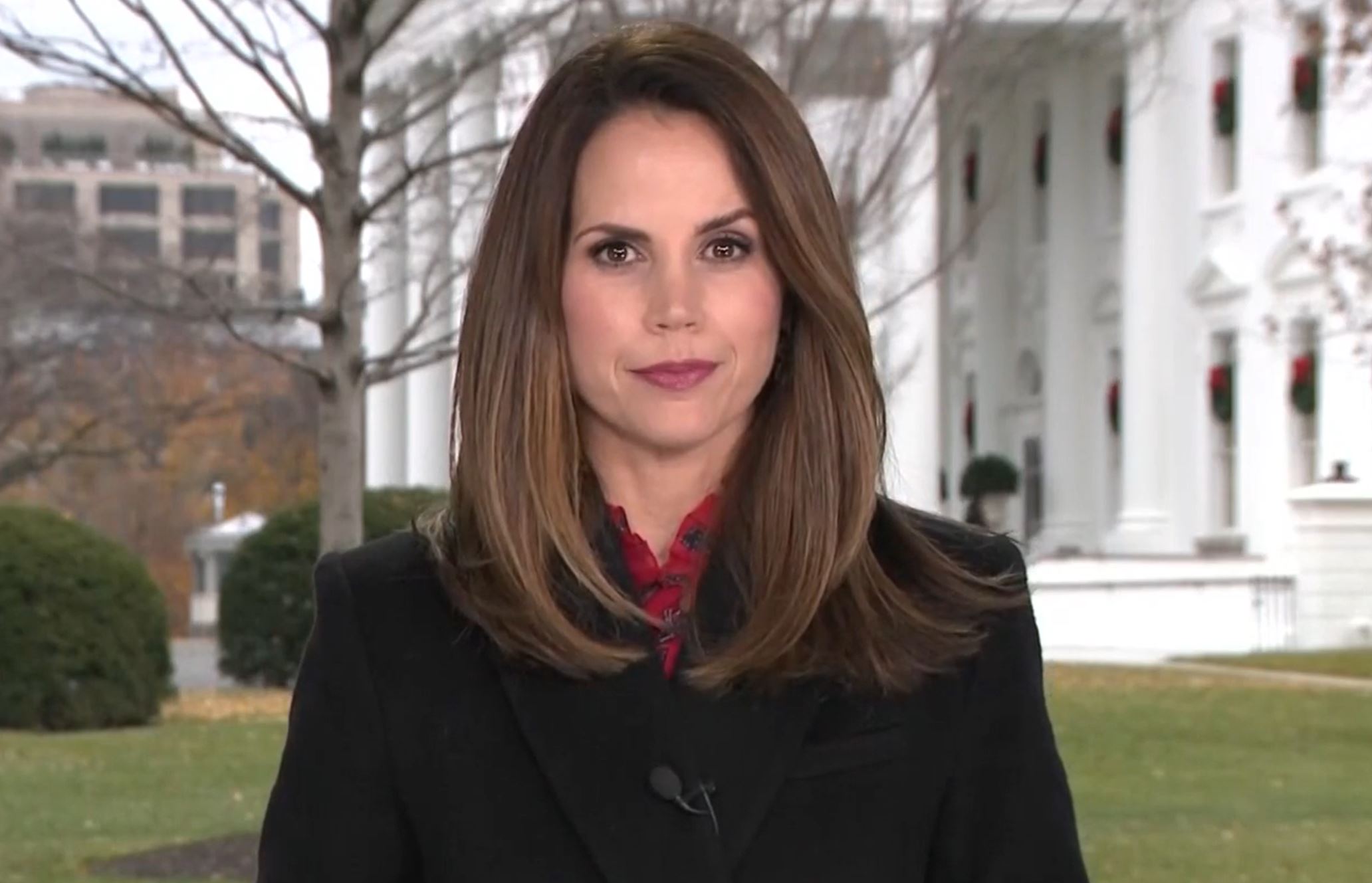

Elena Shao

Reporter, San Francisco

Elena Shao is a fellow at Inside Climate News and reports on environmental justice. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area and is a PhD student in Stanford University’s journalism program. You can also find her work in CalMatters, the San Francisco Chronicle, and the Wall Street Journal.