For early Twentieth century Blacks, resistance meant transferring out | Black Historical past

In 1920, Mallie Robinson and her five children—Edgar, Frank, Mack, Willa Mae, and Jackie Robinson—arrived at the train station in Cairo, Georgia and made their way to Pasadena, California.

Most know that Jackie went on to become No. 42, the black Hall of Famer who would integrate 20th-century Major League Baseball. Few know the situation the Robinsons escaped when they left Georgia that day. They were sharecroppers, earning such a tiny living wage in such a hostile environment that Robinson’s biographer, Arnold Rampersad, said it “smelt of slavery.”

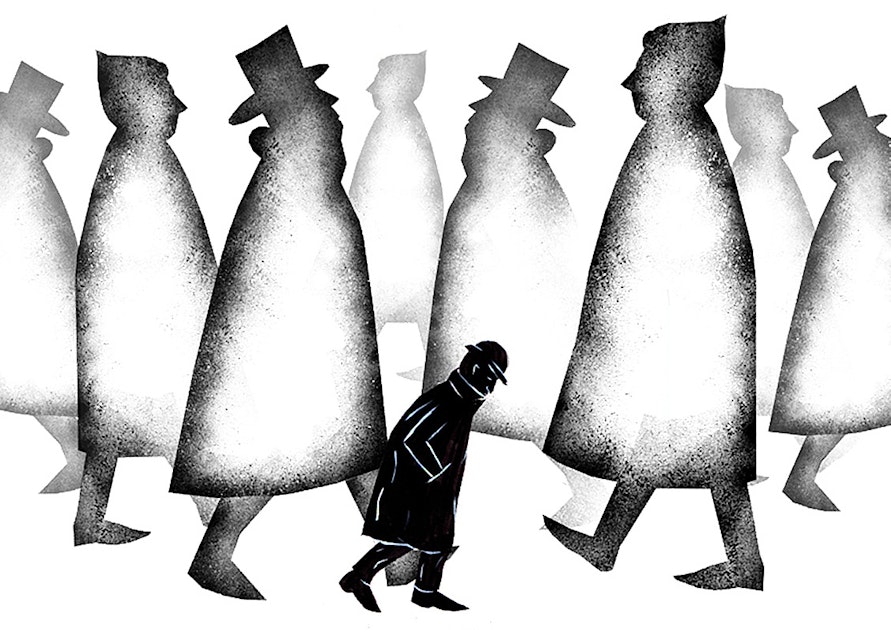

Rampersad wrote that black migrants were harassed at train stations by whites and the police to prevent the loss of cheap labor that was the region’s economic engine. These powers also fell on the Robinsons.

“At the Cairo train station, some white police officers defiantly checked tickets and roughly kicked suitcases and boxes,” Rampersad wrote. “But they didn’t do anything to stop Mallie’s party from going.”

Stealing away from Georgia, the Robinsons joined an early wave of the Great Migration of 1916-1970, in which six million black people left the rural South for fair treatment and better opportunities in the Northeast, Midwest, and Western United States to search.

This mass but sporadic exodus was a form of resistance to the crippling poverty and lack of economic opportunity, segregation, degradation, and violence permitted by the Jim Crow laws that pervaded the South. Lynchings and racial massacres caused many people to flee to safer and better environments. This violence was often a form of voter repression used to deny political representation to America’s Southern blacks, another reason that resisting meant moving away.

“The Great Migration was one of the greatest migrations in the history of the United States,” according to the National Archives. “The driving force behind the mass movement was to escape racial violence, pursue economic and educational opportunity, and break free from Jim Crow’s oppression.”

The cities that received the most transplants included New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Baltimore, Washington, DC and later California, Washington State and Oregon’s largest cities. These cities were the epicenter of the American cultural and economic movement that followed these migrants. African Americans established their own communities and havens in these cities.

“In 1900, about 90% of black Americans still lived in the Southern states,” according to a US Census Bureau report entitled Migrations – The African-American Mosaic Exhibition – Exhibitions (Library of Congress).

“Between 1910 and 1930, the African American population in the northern states grew by about 40% as a result of migration, mostly in the big cities.”

At the end of the migration, only half of the country’s African American population lived in the South, with the rest spread across the North, Midwest, and Far West, causing them to transition from rural to urban dwellers. This was also seen in the South, where African Americans moved from rural to urban areas.

The start of World War I also contributed to the migration of African Americans to the north. In 1914, over 1.2 million European immigrants arrived, compared to just 300,000 the following year. Recruitment of workers in the military has also affected labor availability, multiple sources said. This provided African Americans with employment opportunities in the North during the war, as Northern industries sought a new source of labor from the South. The drop in European immigration has created thousands of jobs in steel mills, railways, meat processing plants and the automotive sector.

“When war production was in full swing, recruiters lured black Americans north, to the dismay of white southerners. Black newspapers — notably the widely circulated Chicago Defender — ran ads touting the opportunities in northern and western cities, along with first-person success stories,” History.com said.

This was reinforced by employment agencies actively recruiting in the South. These companies also offered relocation incentives such as free transportation and affordable housing.

Better wages and living conditions resulted from migration north. The income could be more than double what could be earned from shareholding in the South.

By 1970, cities were home to more than half of the African American population. Black immigration to America was greater than Italian, Jewish or Irish immigration and, unlike these groups, was caused by American politics. For many blacks, this meant leaving the only home they and their ancestors had ever known.

The Exodus came in two waves. The first wave occurred from 1910 to 1940, when about 1.6 million people moved to northern cities from the South, and the second wave occurred after the Depression, when about five million people moved north and west.

The second migration took place around World War II. Main destinations were again major cities like Philadelphia, St. Louis, Denver, Detroit, Kansas City, Pittsburgh and Indianapolis. In the second migration, African Americans also moved further west, flocking to cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland, Phoenix, Seattle, and Portland.

While the search for political and economic equality fueled the Great Migration, it was often guided by public transportation. Many blacks followed popular train routes, bus routes, and highways, historians said. Interstate-95 on the east coast, for example, is a direct shot from Florida to Maine, meaning many African Americans from the Southeast, say Georgia or the Carolinas, drive due north to Philadelphia. Likewise, many from Mississippi and Alabama ended up in Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit.

Because of their proximity to Louisiana and Texas, Los Angeles and San Francisco received the most migrants from those states. In addition, once family members settled in certain cities, their relatives and conspecifics soon followed, according to the National Archives.

The auto industry employed many African Americans, particularly during the war effort. For example, the Ford Motor Company in Detroit converted its factories to produce military jeeps. Hillerich & Bradsby Company of Louisville, Kentucky, famous for making baseball bats, namely the Louisville Slugger, retooled to make rifle stocks for the M1 Carbine, reported Kamila Kudelska for the Buffalo Bill Center of The West.

Due to the Second World War, there was again a labor shortage. African Americans filled the labor shortages in these industries. Originally, these jobs were not open to blacks, but as the needs of the Department of Defense grew and activists like A. Phillip Randolph, one of the most powerful labor leaders in the country, threatened a huge march on Washington if blacks were barred from these positions, the Fair Das The Employment Practices Committee was founded by Franklin D. Roosevelt and the industry began assimilating African-American workers, the National Archives reports.

The Great Migration had an impact not only on industry but also on American culture and art. The migration led to the Harlem Renaissance. The migration also expanded black music, particularly the blues. Racism drove blues singers up the Mississippi Delta to Chicago. Among those who made the transition were Muddy Waters, Chester Burnett and Buddy Guy.

“I considered moving to Chicago where I could avoid some of the racism and have an opportunity to do something with my talent,” Eddie Boyd told Living Blues magazine. “It wasn’t Peaches and Cream in Chicago, but it was a lot better than where I was born.”

The transition was easy. This was mentioned by Isabel Wilkerson in her book The Warmth of Other Suns. She tells readers in the book how six million black Southerners fled Jim Crown to new environments. Many people have struggled to adjust to the faster pace and colder temperatures of the north compared to the south.

One thing is certain, the African American workforce helped build much of the infrastructure in most metropolitan areas and helped grow this country’s industries, proving once again that America could not have prospered without the African American workforce.