Doug Burgum ‘guess the farm’ on a software program agency. Now he is betting his enterprise savvy results in the White Home. – InForum

FARGO — Doug Burgum is about to enter a crowded field of candidates vying for the Republican presidential nomination as an unknown figure on the national political stage.

But one early job on Burgum’s resume could help the dark-horse candidate stand out: chimney sweep.

While attending North Dakota State University, Burgum hired himself out as a chimney sweep. The unusual occupation was featured in the student newspaper, with a photo of Burgum, in top hat and tuxedo on a snowy roof, and was picked up by a wire service.

The admissions office at Stanford University saw the article — and Burgum was admitted to its master’s of business administration program.

There, he met Steve Ballmer, who would go on to become CEO of Microsoft and an influential business adviser for Burgum.

After a stint as a consultant at McKinsey & Co., Burgum mortgaged a quarter section of farmland homesteaded by his grandfather to invest $250,000 in a fledgling business software firm called Great Plains Software in 1983.

Burgum, having bet a good part of his inheritance, was unnerved to learn that the business software industry then in its infancy was crowded with competitors, but was able to distinguish his firm with top-notch customer service, a lesson learned from his family’s grain elevator business in Arthur.

The willingness to take a big risk — moderated by working assiduously to improve his odds of success — would prove to be an attribute that would help define Burgum’s rise in business and his later career as a politician.

“Betting the farm,” as Burgum later would describe his source of startup capital, would prove to be a good wager. When Great Plains broke ground at its south Fargo campus, Burgum harnessed a horse-drawn plow to mark the occasion.

Doug Burgum, center, is pictured in 1992 at Great Plains Software.

Dave Wallis/The Forum

In 2001, less than two decades after Burgum tied his future to Great Plains, with Ballmer at its helm, Microsoft bought Great Plains for $1.1 billion. Burgum stayed on as a Microsoft senior vice president until 2007, then turned his focus to serving as an investor and director on the corporate boards of early-stage software companies.

Freed of the responsibilities of running a company, Burgum also took his business chops in a new direction, real-estate development, which would allow him to indulge his interest in architecture.

He had formed a company, Kilbourne Group, named after his mother’s maiden surname. When Burgum was a boy, his mother took him on walks through downtown Fargo, pointing to notable buildings and telling him their background — a history lesson that helped to inspire what would become a major private downtown renewal project.

Kilbourne Group bought and renovated many distinctive downtown landmarks, including the Black Building, and built the 23-story RDO tower.

It became Fargo’s tallest building, although deliberately shorter than the skyscraping state Capitol, striking a note that was audacious and restrained at the same time.

Doug Burgum talks in 2013 about the restoration process of the Loretta Building overlooking downtown Fargo.

David Samson / The Forum

One of the buildings Kilbourne Group acquired and renovated, the former St. Mark’s Lutheran Church, became the Sanctuary Event Center, where on Wednesday, June 7, Burgum will take the stage to announce his candidacy for the Republican nomination for president.

As a real estate developer, Burgum preached the virtues of dense, downtown development as a way to enliven communities, prevent urban sprawl and save money by avoiding the need to extend expensive public infrastructure and services to the city’s fringe.

Later, as governor, he would promote the same themes through his Main Street initiative, saying that communities must offer attractive amenities to attract workers.

Burgum has made philanthropic contributions, including his family’s support of the Plains Art Museum and his donation of the former Northern School Supply building to his alma mater, NDSU, which became Renaissance Hall, which houses the university’s visual arts department and much of its architecture department.

Although a campaign contributor, Burgum was never visibly active in politics until he entered the 2016 governor’s race after Jack Dalrymple announced that he wouldn’t seek a second term, leaving an open seat.

Fargo entrepreneur and philanthropist Doug Burgum, third from right, meets with the press following his announcement for North Dakota’s gubernatorial race on Jan. 14, 2016, in Fargo.

Michael Vosburg / Forum Photo Editor

But a major obstacle stood in his way: Wayne Stenehjem, who had served more than 20 years as attorney general and was the presumptive Republican nominee.

Burgum entered the race trailing by almost 50 points. He sought the endorsement at the party convention, not expecting to win, he said, and finished third.

During the convention, Burgum played up to his outsider image by lecturing the delegates, many of them state legislators, whom he criticized for allowing state government spending to balloon unsustainably on their watch.

His strategy all along was to win the GOP primary, and he made a point of visiting every community in the state with at least 1,000 people, often talking to very small gatherings, especially at first, and filling notebooks with ideas from his encounters with voters.

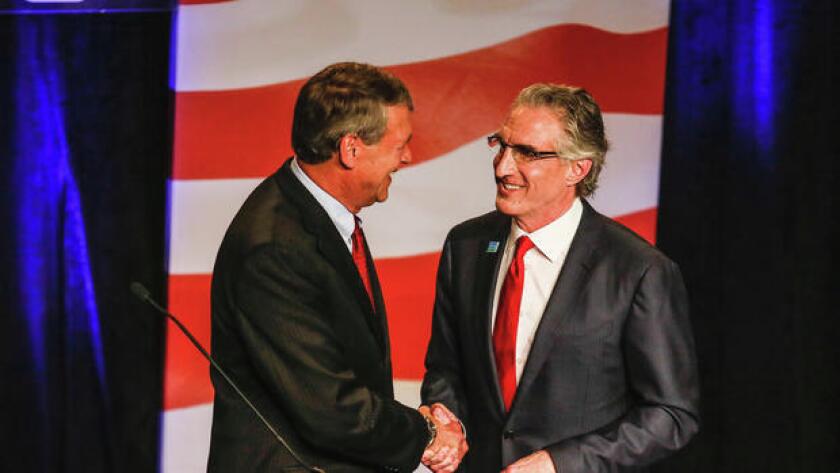

North Dakota Attorney General Wayne Stenehjem, left, and Fargo businessman Doug Burgum shake hands at a gubernatorial debate in 2016.

Rick Abbott / The Forum

Burgum roared back from his drubbing at the convention with a convincing victory over Stenehjem, taking 60% of the vote in the primary — and cruising on to beat his Democratic rival by capturing more than 76% in the general election.

Some of Burgum’s famous friends from his time at Microsoft were among his prominent financial supporters during his first campaign for governor. Microsoft founder Bill Gates contributed $107,000 and Satya Nadella, who succeeded Ballmer as Microsoft CEO and who had worked under Burgum at Microsoft’s Fargo campus for 5½ years, donated $10,000.

During the campaign, Burgum ran as an entrepreneur and businessman, with a pitch that he was the right person to apply his tech savvy to reinvent state government through greater efficiency, and to help diversify the economy, too reliant on energy and farm commodities subject to whipsawing price swings.

Once in office, Burgum sometimes clashed with the Republican-dominated Legislature. Although he pledged party unity after winning the divisive primary contest with Stenehjem, Burgum didn’t shy away from tangling with those in his own party.

Burgum showed himself willing to dip into his personal fortune to fund a political group that worked to defeat fellow Republicans who had resisted his initiatives, most prominently former Rep. Jeff Delzer, R-Underwood, who had been the powerful chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, who was at odds with some of Burgum’s spending priorities.

During the 2022 election cycle, records showed Burgum gave at least $935,000 to the Dakota Leadership PAC, which ran an advertising blitz against Delzer, who lost the GOP primary endorsement. Burgum spent much more in 2020, bankrolling the group’s ad campaign with contributions of more than $3.2 million.

Burgum’s internecine quarrels rankled some of his fellow Republicans, some of whom were legislators who were in a position to make their displeasure known, but Burgum didn’t alter course.

As governor, Burgum has championed energy policy. Unusual for a Republican, he set a goal of using innovation and incentives to achieve carbon neutrality in North Dakota by 2030, exploiting North Dakota’s policy and geological advantages in storing carbon dioxide deep underground.

North Dakota Gov. Doug Burgum delivers his annual State of the State address on Jan. 3, 2023.

Jeremy Turley / Forum News Service

He boasted that as of 2021 companies had responded by pouring $25 billion of investments into energy initiatives in the state.

In contrast to many of his fellow Republican governors, Burgum’s response to the public health threat posed by the COVID-19 pandemic included support for vaccination and, in the early days of the pandemic, targeted business shutdowns and a mask mandate as measures to prevent hospitals from being overrun with cases.

Chafing at the state interventions, the Republican-dominated Legislature responded in 2021 by passing a law allowing legislators to call a special session, with the power to “terminate, extend, or modify” a state of disaster or emergency declared by a governor.

North Dakota Gov. Doug Burgum receives a first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine at the Bismarck Event Center on March 9, 2021.

Jeremy Turley / Forum News Service

Burgum’s drive for efficiencies in state government draws upon his background in technology and business.

He sounds like the McKinsey consultant he once was when he makes the case for better cash management of state funds, and he sounds like a former software executive when he rhapsodizes about the need for information technology upgrades that are more consumer friendly.

Burgum has never emphasized socially conservative positions and has generally refrained from joining the “culture war” debates that animate many in a party dominated by Donald Trump. In 2020, Burgum said the state Republican Party’s position on LGBTQ issues was “divisive and divisional.”

Still, in the recently completed legislative session, Burgum signed a near-total abortion ban bill as well as several laws restricting transgender rights. Earlier, in 2021, he signed a law banning the teaching of critical race theory in North Dakota public schools.

North Dakota leaders shouldn’t forget that the state is in constant competition for capital and for talent — skilled workers — and be seen as welcoming both, he has said.

Burgum has twice been endorsed by Trump, and has endorsed the former president he now is challenging for the nomination. He has said he would vote for Trump if he is the Republican nominee in 2024, a choice he regards as preferable to President Joe Biden, the likely Democratic nominee.

Gov. Doug Burgum talks about his vision for North Dakota on April 19, 2018, while meeting with The Forum’s Editorial Board.

David Samson / The Forum

In seeking the nomination, Burgum is betting that what he has called a “silent majority” of voters who shun the ideological fringes would welcome a pragmatist over a divisive ideologue. He knows that he will have to overcome his underdog status as a governor of a small, rural state who is unknown in national politics.

“There’s a value to being underestimated all the time,” Burgum said, recalling that he had no endorsements in his first race. “That’s a competitive advantage.”