Cross-cultural validation of Malay model of perceived professionalism amongst dental sufferers

The study aimed to validate the Malay version of the Perceived Professionalism questionnaire for dental patients. The final questionnaire had 20 items and underwent translation to the Malay language. Maintaining the validity and reliability of instruments and scales in questionnaire translation is crucial for cross-cultural adaptation [17]. The literature has proposed a six-step model for cross-cultural adaptation of an index [18]. These steps include ensuring conceptual, item, semantic, operational, and measurement equivalence, which collectively enhance the validity and reliability of assessments in diverse cultural contexts. Achieving functional equivalence requires success in all types of equivalence [19, 20].

The meticulous evaluation of the questionnaire by the research team, leading to the exclusion of item no. 24 due to its inapplicability to the Malaysian population. Item no. 24 of the original questionnaire displayed male dentists in different clothing, requiring respondents to select an image of a dentist they would prefer receiving treatment from. Given that Malaysia is a melting pot of three diverse cultures [21, 22] Malay, Chinese, and Indian, the definition of standard professional attire can vary significantly. Moreover, with the proportion of female dentists nearly doubling that of male dentists in our country, the item could potentially reflect a gender bias, rendering it unsuitable for inclusion. Owing to the challenges associated with representing all appropriate attires in visual form within the questionnaire, we made the decision to eliminate this item. This highlights the importance of contextualizing assessment tools for different cultural settings. This decision was in line with best practices in cross-cultural research, ensuring that the instrument is culturally sensitive and meaningful.

In our study, the high CVI scores, ranging from 0.75 to 1.00, along with robust Kappa values (0.72–1.00), suggested that all retained items possess excellent content validity for both relevance and clarity [23, 24]. The correction of certain items (1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 17, and 22) and incorporation of two new items (No. 24 and 25) based on expert feedback was a notable aspect of the face validity assessment and ensures that the questionnaire aligns with the cultural nuances that may have been overlooked in the original version and specifics of the dental profession in Malaysia. The new item no. 24 was included to gauge patients’ opinions on whether the dental team should be permitted to create and post videos of clinic events involving patients on social media without their explicit consent, considering the widespread reliance of the public on social media for information and the use of social media by dentists for marketing [25]. Additionally, the new item no.25 was aimed to investigate if patients felt it was pivotal to be provided a channel for complaints and feedback at dental clinics to enhance service quality [26]. By assessing their perspectives, the data could then be used to potentially enhance dental services for upcoming patients as well as for themselves seeking treatment in the future.

Technical equivalence refers to data collection methods and procedures being comparable across languages and cultures using the same tool [27]. The process involved forward-translation, evaluation by an expert committee, back-translation, re-evaluation, and pre-testing among patients [27]. Forward translation preserves the original questionnaire’s meaning and intent, while back translation involves a different translator to identify discrepancies. In our study, two native Malay-speaking translators completed the forward translation: a public health dentist and a paediatric dentist. Before reaching a consensus version, the core research team evaluated these two forward-translated versions. Two independent English-speaking translators, who were experts in public oral health and also fluent in Malay, back-translated the questionnaire from the consensus version into English. Back-translated English version was then contrasted with the source language to establish conceptual and semantic comparability. The Malay version of the questionnaire was completed in accordance with the suggestions made by the core research team.

Validation involves testing the questionnaire in the target culture, including Cognitive de-briefing, statistical analysis, and expert review [28]. The Malay version was finalized and pre-tested on fifteen patients at two university dental clinics. There were no difficulties in comprehension during the pre-testing of the questionnaire. This underscores the precision and appropriateness of the translated items in capturing the intended construct of perceived professionalism among dental patients within the Malaysian cultural context.

The sociodemographic characteristics of respondents provide valuable insights into the diversity of the sample. The predominance of female respondents in both the EFA and CFA samples reflects the common trend of higher female representation in healthcare-related studies, which aligns with the demographics of Malaysian dental patient populations [29]. The age group of 18-24 constitutes the largest proportion in both samples. This skew towards a younger age group may reflect the overall demographics of dental patients or suggest a greater willingness among younger individuals to participate in research. This finding was in accordance with a study by Tan, YR et al., who reported demographic and socioeconomic inequalities in oral healthcare utilization by Malaysians [29]. The Chinese ethnic group was prominently represented in both samples, followed by the Malay group. Understanding the perceptions of different ethnic groups is crucial for the cross-cultural validation of the perceived professionalism questionnaire, as cultural nuances may influence responses [30].

The majority of respondents in both samples were single. This distribution may have implications for the perceived professionalism construct, as marital status can influence healthcare-seeking behavior and expectations from healthcare providers. A significant proportion of respondents in both samples fall within the <RM5000 income bracket. This socioeconomic diversity was relevant in assessing whether perceptions of professionalism vary across different economic strata. A notable proportion holding a degree in both samples suggests the influence of health literacy and, consequently, perceptions of professionalism towards dentists. The overwhelming majority of respondents had visited a dentist or received dental treatment before. The high level of previous dental experience ensures that the perceptions captured in the questionnaire are grounded in real-life encounters with regard to dental professionals [31].

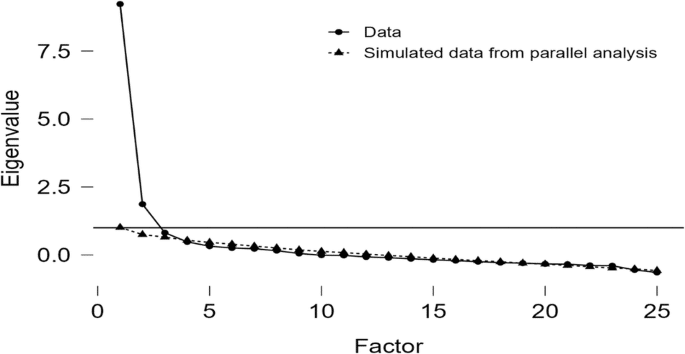

The implementation of EFA yielded meaningful insights into the factor structure and underlying components influencing patient perceptions. The KMO value of 0.903 indicates a highly suitable dataset for factor analysis, emphasizing the adequacy of the sample for the examination of factor structures. The significance of Bartlett’s test further supports the appropriateness of applying factor analysis to the dataset, given the correlation matrix’s departure from the identity matrix [32]..

The EFA revealed that the items were grouped into three distinct components; Patient expectation of a dental care provider, Ethics and Dentist’s professional responsibilities, and Patient communication and confidentiality. Under the component of ‘patient communication and confidentiality’, two new items pertaining to posting videos in social media without patient consent and an avenue for obtaining feedback and complaints. The factor structure was slightly different from the original questionnaire which had four factors; namely Excellence and communication skills, competence to practice, humanism and service mindedness and dentists duties and management skills [4]. The diverse ethnic composition of Malaysia contributes to the differing perspectives through which patients may interpret the contents of a questionnaire. Each cultural group, such as Malay, Chinese, Indian, and indigenous communities, holds unique values, beliefs, and norms that impact their views on professional behavior, communication styles, preferences, and healthcare practices. For instance, different ethnicities may either place varying levels of importance on a dentist’s authority and expertise, or on their warm and friendly demeanor. Moreover, specific cultural beliefs about oral health can also affect patients’ expectations and perceptions of dental care. Recognizing and understanding these cultural nuances are essential for evaluating how patients assess the professionalism of dental practitioners in Malaysia.

Three items were removed in this study due to cross-loading (Q14), negative loading (Q23), and low loading factor (Q8). The same items had lower ranking in the list of important elements of dental professionalism in the original study [4] Similar themes of perceived professionalism by patients were noted in other studies [2, 5]. The factor loadings for items exhibit substantial loadings, indicating their strong association with the respective components [33]. The Eigenvalues and the percentage of variance explained by each factor provide additional clarity on the relative importance of each component in explaining the overall perceived professionalism among dental patients. Reliability analysis using alpha Cronbach coefficients demonstrated strong internal consistency for all three factors, with values ranging from 0.768 to 0.913, exceeding the standard threshold of 0.70 suggesting that the retained items within each factor reliably measure the underlying constructs of professionalism [34].

The CFA conducted in the second dataset (n = 160) to validate the factor structure identified through the EFA in the initial dataset. The modified model demonstrated a good fit, as indicated by the χ2/DF ratio of 1.99. The values of other fit indices, such as the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI = 0.84), Comparative Fit Index (CFI = 0.90), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR = 0.06), also suggest an acceptable fit. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), falling within the recommended range (0.08), further supports the model’s adequacy. The measurement model indicated that, after modification, all items had standardized loadings above 0.5, except for Q19, which was subsequently removed in the final model. This suggests that most items reliably measure their respective constructs within the modified model, meeting the conventional threshold for satisfactory item loading. The assessment of reliability using CR demonstrated acceptable internal consistency among items for each component. The range of CR values (0.741 to 0.897) indicates robust reliability within each construct.

Convergent validity, assessed by Average Variance Extracted (AVE), indicated that all three components reliably capture a significant amount of variance from their respective sets of items. The standardized loadings for items within the component 1: Patient expectation of a dental care provider (Q11, Q12, Q13, Q15, Q18, Q19, Q7, Q9, Q20, Q21, Q25) all surpassed the acceptable threshold of 0.5, except for Q19, which was removed due to its lower loading factor. The reliability and convergent validity of this component were well-established. The items within component 2: Ethics and Dentist’s professional responsibilities (Q17, Q2, Q3, Q4, Q5, Q6, Q1) exhibited standardized loadings exceeding 0.5, demonstrating their reliability and contribution to the underlying construct. The reliability and convergent validity for Component 2 were notably strong. Lastly, the items in component 3: Patient communication and confidentiality (Q16, Q22, Q24) demonstrated acceptable standardized loadings, reliability, and convergent validity, contributing to the overall construct.

The HTMT ratio of correlations was employed to evaluate the discriminant validity to ensure that the constructs measured by the instrument were distinct from each other. The HTMT values for Component 1, 2, and 3 were below the threshold of 0.9, indicating satisfactory discriminant validity [16]. The HTMT values of 0.867 between Component 1 and Component 2, and 0.337 between Component 2 and Component 3, fall below the recommended threshold, signifying that these constructs are distinct from each other. The successful demonstration of discriminant validity provides assurance that the Malay version of the questionnaire effectively captures distinct facets of professionalism among dental patients. It is crucial for the instrument to differentiate between these components, as it ensures that the factors measured are not overlapping and contribute uniquely to the overall construct of perceived professionalism.

The modified measurement model is a refined version based on the outcomes of the CFA. This model incorporates feedback from the exploratory phase, displays a satisfactory fit with the data. The fit indices, such as χ2/DF, GFI, CFI, SRMR, and RMSEA, collectively indicate an acceptable fit of the model.

This study is not without limitations. Firstly, the gender representation in the sample population is imbalanced and the age range is not wide enough to represent the entire Malaysian population. Secondly, comparative analysis between the original 4-factor model and the proposed 3-factor model could not be done. Such an examination would afford a comprehensive discussion on the cultural disparities inherent in the questionnaires.