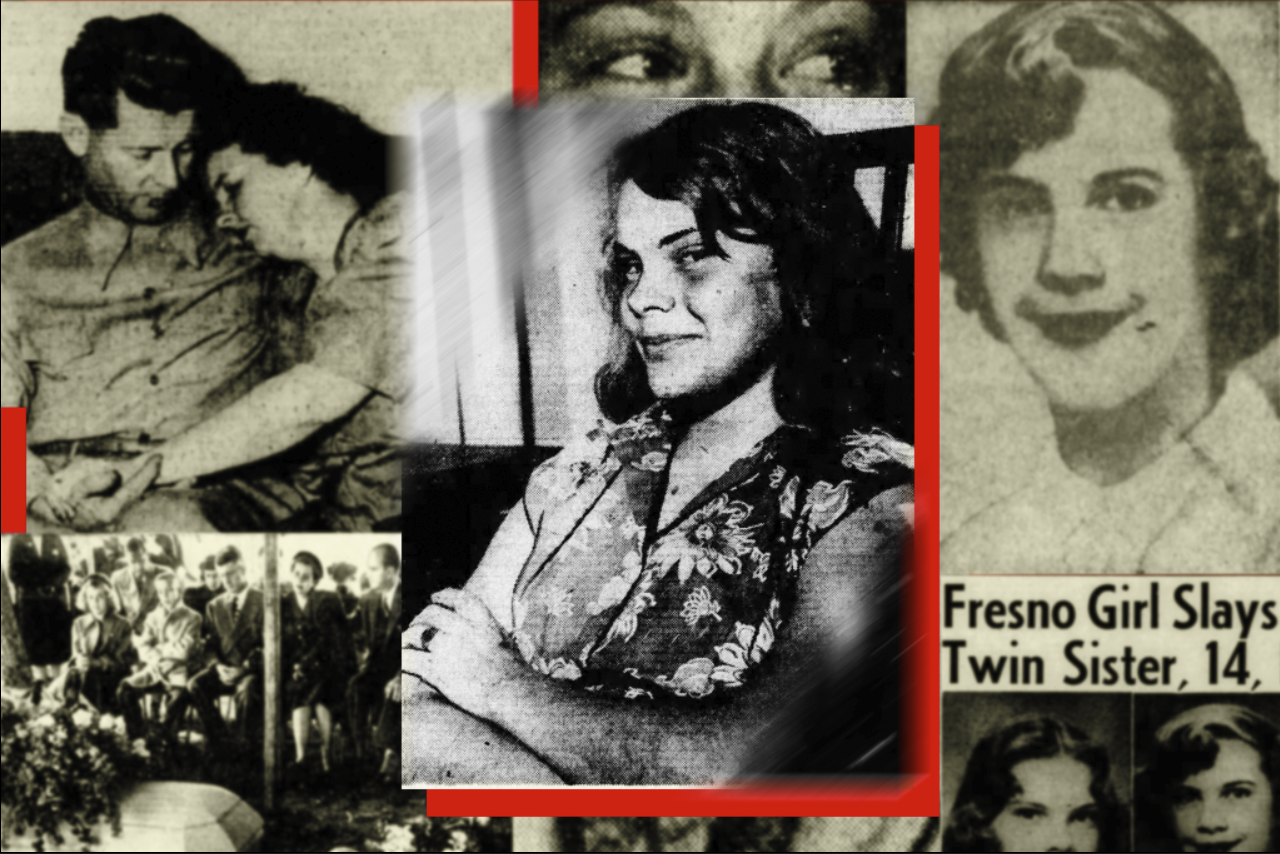

The California woman who killed her twin

Fourteen-year-old Alice was usually a good student, bright and popular. But her teachers at San Joaquin Memorial High School noticed her grades were dropping. She kept having to drop out of class to recover from her migraines. Alice was “very moody, very nervous and a little despondent,” one teacher told the Fresno Bee, but so were many teens. Only later, the teacher recalled with regret, did everything read like a warning sign.

At 1:45 am on March 19, 1950, Alice and her twin sister, Sally, came home from babysitting. At the six-room ranch-style home on Harvey Avenue in Fresno, silence fell as the Richard family fell asleep.

At 3 a.m. Alice got up. She searched in the dark and found the family’s bolt-action rifle and two cartridges. She padded back into the bedroom, handed the rifle to her sleeping twin, and pulled the trigger. Alice went to the nearest phone and called the police.

“Come to 4721 Harvey immediately,” she said. “There has been a murder.”

—

A twin killing its twin is so rare even today that there are only a handful of documented cases. When Alice killed Sally, the act was unknown.

The news made Alice a household name, her face gracing front pages across the country. It caused such panic that many newspapers reported on a report by a psychologist reassuring parents that their children were not murderers.

“This is an exceptional case,” wrote the doctor. “In the scientific records of twin studies, both in Europe and America, I could find no other instance of one killing the other twin.”

Sally and Alice were born in Long Beach in 1935 and were nine years old when the family moved to Fresno. From the outside, there seemed nothing particularly remarkable about the Richards. Father Edgard was a plumbing salesman and Mrs Mary was busy raising their six daughters and two sons.

Friends and family painted a tense portrait of the girls. By most accounts, Alice was the more popular and powerful sister. Her 16-year-old brother told the Fresno Bee he couldn’t imagine Alice envying Sally. “Alice looked better and I could imagine Sally being jealous of her,” he said. Sally was described as “exuberant”. “That’s why the girls didn’t invite her to parties,” the brother commented. “Since she and Alice were twins, Alice wasn’t invited either.”

Sally and Alice argued, but most shrugged – what 14-year-old siblings don’t fight every once in a while? However, at least one family member feared that the situation would escalate. Her 13-year-old brother told investigators he recently overheard the girls’ argument. “I’ll kill you,” he heard Alice shout, “and I’ll kill you with a gun.”

“I was afraid she was serious, so I got the .22,” the boy told investigators. He hid the gun under his bed.

The night Sally died, the twins were babysitting their neighbors’ two young daughters. Sally was usually alert, but this evening she seemed busy. She followed her neighbor through the house, pretending to be about to share a secret. When it came time to pay the girls, the neighbor only had a $5 bill. She joked she would have to rip it up to give half each to Alice and Sally.

“She won’t need it,” Alice replied.

When the police arrived on Harvey Avenue a few hours later, they found Alice calm amidst the chaos. When asked why she killed her twin sister, she remained calm.

“I killed her,” Alice said, “because I hated her.”

“She told me I could ask questions for the rest of my life and I would never find a reason other than the one she gave,” a sheriff’s deputy told The Bee.

When Alice was in custody, she kept up the ice-cold facade. She complained that Sally was “loud, acted like a weirdo and sang at the top of her lungs”. She said she enjoyed her stay in the juvenile detention center and slept better than she had in years. “The only thing I have to complain about here,” she boasted in her first court appearance, “is that they don’t allow us to use lipstick.”

Crowds of reporters and photographers followed her every step. Alice’s outfits, hairstyles and jokes have been breathlessly printed across the country as if she were a much older femme fatale. It was a circus.

In the rush, the sorrow of the situation was lost. A juvenile judge ordered Alice to undergo extensive psychological evaluations. Her parents agonized over her mental state and wondered if they had missed signs. Her mother told reporters she couldn’t imagine the act was premeditated; She said Alice asked earlier that evening for clean stockings to wear to church the next day – hardly the act of a girl who would murder a sibling hours later. Her father Edgard was convinced that Alice’s mental state had changed.

“I am satisfied that she is ill and unaware of the seriousness of what she has done,” he told the Bee days after the murder. Her family attorney seemed to agree. “I asked her if she knew the difference between right and wrong. She said she did it,” the attorney said. “… Almost in the same breath she will say that she was still right to kill Sally and that she would do it again.”

When the psychiatric evaluation came back, experts said Alice was in some sort of mental crisis. In a surprisingly progressive move for 1950, the judge did not allow her diagnosis to be disclosed. He felt that the only hope Alice had for getting her condition under control was to get out of the spotlight again. He decided that she would be checked every 90 days until she was well enough to be released. Alice was taken to Napa State Hospital for an indefinite stay.

“It’s bad enough losing a daughter,” her father told the media, “but in this case, I actually lost two.”

—

Although the adults in her life tried to keep her out of the public eye, Alice wasn’t done with it. In August, four months after being sent to Napa, she climbed a fence and set out in search of freedom. Almost immediately she recognized the car driving up the street – it was her mother, coming to visit. Alice ducked sideways and waited for her to come over.

A view of Market Street in San Francisco from a 35mm slide taken in the 1960s.

Meghan Bennett/Getty Images/iStockphoto

Four different cars picked up Alice on her way to San Francisco. With $3 in her pocket, she strolled down the market, saw a movie, and bought a soda and donut. But freedom wasn’t what she expected. Out of money and without a place to live, Alice went to the mission’s police station.

“I’m Alice Richard,” she announced. “I’m a runaway from the hospital in Napa. I shot my sister.”

She was brought back to Napa and was out of the limelight for the rest of her life. Eventually, Alice left the state hospital, but there were no crowds photographing her last day. Whatever happened happened quietly and quietly. There is no record of what Alice did next, but obituaries fill in the rest. She married and moved to Alaska, where she died in 2014 at the age of 78. She is buried next to her husband in the island town of Sitka off the Alaskan coast.

More than 1,500 miles away, her sister Sally rests in Fresno. Her funeral took place three days after her death; Alice decided not to go.

Schoolmates left Sally’s coffin covered with red roses and white carnations. A pastor gave her eulogy.

“We cannot fathom or understand what God had in mind when He brought such calamity upon us,” he said. “Perhaps such a great tragedy should not be understood by us.”