Column: Newsom cares extra about almond growers than California’s salmon fishery

SACRAMENTO —

Governor Gavin Newsom bills himself as a protector of wildlife, so you wouldn’t think he takes water from baby salmon and there are almonds.

Or with pistachios or cotton or alfalfa.

Especially as California just got drenched in the wettest three-week streak of storms on record and headed for another powerful snow and rain cloud.

But Newsom and his water officials still claim we’re suffering from a drought – apparently it’s a never-ending drought. So last week they used this as a reason to drastically reduce the river flows needed by migrating small salmon when the water is needed to irrigate crops in the San Joaquin Valley in the summer.

Still calling our wet weather a drought is a shameful distortion of a word — a propaganda tool aimed at convincing people that they should continue to conserve water. People should, but don’t have to, be addressed like children.

What Newsom and government officials are really talking about is a long-term water shortage. It is caused by the fact that California has more agriculture and people than what nature can provide us with can support. And it is made even more problematic by the uncertain prospects of climate change.

But water scarcity doesn’t necessarily mean drought. That means we’re not recycling, conserving and replenishing aquifers enough – and not wisely allocating what we have.

Agriculture uses 80% of California’s tapped water. The rest is allocated for domestic use – business and housing.

Calculated differently, 40% of all water – tapped or untapped – ends up in agriculture and 10% goes into households. The other 50% goes directly into the environment – flowing down rivers, irrigating what’s left of our wetlands, and flowing into the ocean. And on their way to the ocean, river courses carry young salmon out to sea, where they grow up.

The Sacramento River is the second largest salmon producer on the West Coast after the Columbia.

But salmon numbers have plummeted along the Sacramento in recent decades, largely due to dams blocking historic spawning grounds and the diversion of water to farms and towns.

Also, the installation in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta messes up the salmon. Huge pumps sending water south through aqueducts maul the critters or drag them into the grips of lurking predators.

Each year there are four salmon spawning runs up the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers. By far the largest is in Sacramento. Autumn is the most important. Last fall, fewer than 62,000 fish returned to spawn, the second-lowest in 70 years. In the previous autumn it had been almost 132,000.

Those are steep declines from 448,000 in 2013 and 873,000 in 2002.

Meanwhile, almonds – one of our thirstiest crops – are thriving. We span up to 1.6 million acres primarily in the San Joaquin Valley. California produces 80% of the world’s almonds. Around two thirds are exported.

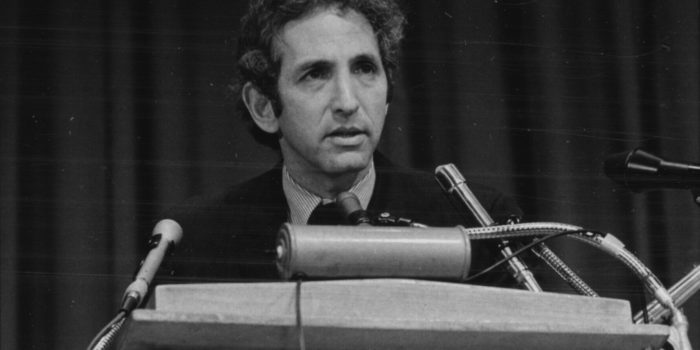

“Salmon numbers have declined significantly in Newsom every year since he became governor, by a third,” says Barry Nelson, a longtime water consultant and environmentalist.

But should Newsom be held responsible? We have experienced a real drought.

“Absolutely,” says Nelson. “No doubt the governor is responsible. He waives standards to protect the salmon. The state’s failure to protect salmon has turned bad news into disaster.”

“In the same four years that the salmon crashed,” adds Nelson, “almond acreage has grown by 320,000 acres.”

Newsom signed an executive order on Feb. 13 allowing salmon protections to be suspended. It was as if we were still suffering from drought and every drop of water was needed for people and food production.

“To protect public health and safety, it is critical that the state promptly take certain emergency measures to prepare for and mitigate the effects of drought conditions,” the governor said in his order.

The governor-appointed State Water Resources Control Board dutifully obligated and suspended a requirement for rivers through the delta’s estuary, which salmon need at this time of year to drive them into the ocean.

The suspension essentially halved flows through at least the end of March. The water is stored in reservoirs.

But the big reservoirs were already filling up from the January storms. And the Sierra’s snowpack was deep — at 173% of normal for the past week.

“It’s not even a drought. If we can’t create good conditions for fish in a year like this, we’re completely bankrupt as resource managers,” says Gary Bobker, director of programs at the Bay Institute, an environmental organization focused on the San Francisco Bay area.

Young salmon – about 4 inches long – need strong river currents to carry them across the delta into San Francisco Bay and out of the Golden Gate.

“They’re bad swimmers,” says John McManus, president of the Golden State Salmon Assn. “They have evolved to be washed down by rivers in the spring like nature does. But that was turned on its head. Now the water will be released for agriculture in the summer.”

This is because agriculture has more political weight.

McManus says the governor “doesn’t answer our calls or doesn’t respond to our emails.”

“The single biggest problem for salmon in California is the lack of spring flow in rivers,” claims McManus.

Maybe 1% make it to the ocean.

Eric Oppenheimer, the deputy chief executive officer of the water board, told me, “We’re not saying that [the flow reduction] has no effect” on Pisces. “We’re just saying that we don’t think the change will result in any undue impact.”

The State Department of Fish and Wildlife agrees in principle.

“At this point, we’re still in a drought,” Oppenheimer said. “Sometimes we find ourselves in a drought and a flood at the same time.”

That doesn’t make any sense to me.

Nor does cutting back the water for struggling baby salmon when it’s pouring rain.